An Embroidery machine is not a ‘thread printer’. Often times we hear that a design looked perfect on the screen, but didn’t sew out that way. It almost never will sew out the way you see it onscreen. As the design sews, thread is being pushed through the fabric, opening it up, tightening it in the hoop, reducing its elasticity and drawing it together. As the fabric moves, the ‘location’ of all subsequent stitches is going to be incorrect by some small amount. This produces various sewing defects such as loss of registration, puckering/gathering, dancing baselines, poor coverage and even fabric tearing. If we pay attention to how we construct the design we can minimize these difficulties, and even use them to our advantage if we are crafty. We also want to allow our objects the ability to move around a bit, and anchor them as needed. It is a process guided by experience. Let’s look at some common issues:

Registration describes the effect in areas where two or more objects meet at their edges. If the objects stitch tightly up against each other so that there is no background color bleeding through, the registration is considered ‘tight’ or correct. As a design is being created, it is worthwhile to think about registration – you can add overlap to your shapes or add compensation which could save you time later when you edit the design.

Switching fabric, project types or even machines and hoops will affect the registration of any design. This is why you often hear that digitizing for hats should be done by a professional – the registration issues compound. The verb ‘compound’ here means that each object that sews will affect the location that the next object will sew. This happens because the fabric gets distorted a little bit for each and every stitch. What you see on the computer screen does not include the distortion that occurs during stitching.

How do you fix it?

You will have to do the same thing that people before you have done; sew, edit, sew, edit, sew until you see the result you need, then try to remember what you did the next time you create a design. It’s a process that gets much easier once you have some real experience, and the only way for that to happen is for you to do it.

Registration issues come in a couple common forms when digitizing.

1.) Outline stitches are separated from filled areas.

There are some tricks to making outlines register. The easiest is not to use them. This is a design style issue, and we see through the years that designs will sometimes come with a double-stitch or bean-stitch outline around everything. There is no rule that says you need to do this. Only use outlines where it is important to make the artwork appear crisper.

Another way to help outline stitches is to give them more body; a bean stitch will work better than a single or double run. A backstitch or stemstitch is wider and therefore naturally going to ‘hide’ any registration issues easier.

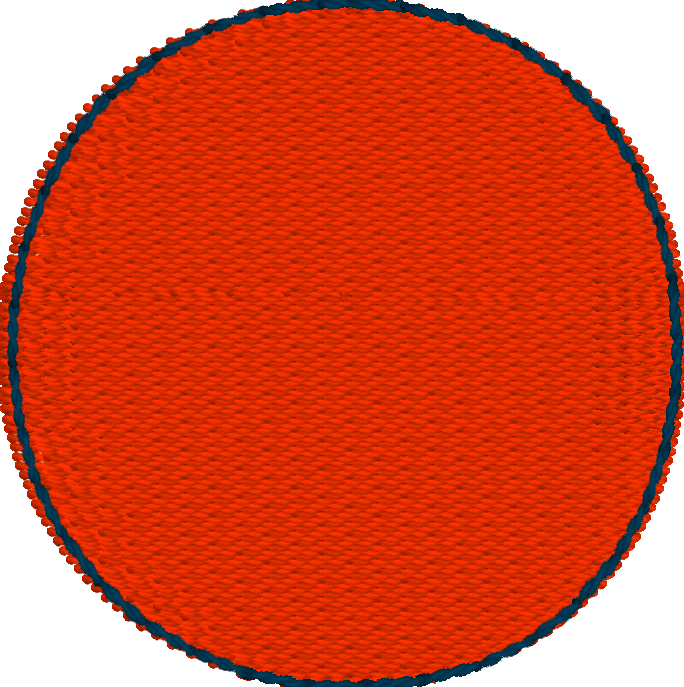

When creating the outline, place your points slightly inset into the stitches that they surround – perhaps only half a needle-width 3-4 stitch points for your first try. All fills and satins tend to ‘draw’ the fabric in because of tension, and the thread has to curve down toward the fabric where the needle penetrates. This causes the outline stitch to be pushed away. Therefore in-setting the outline, if only slightly, will help the result.

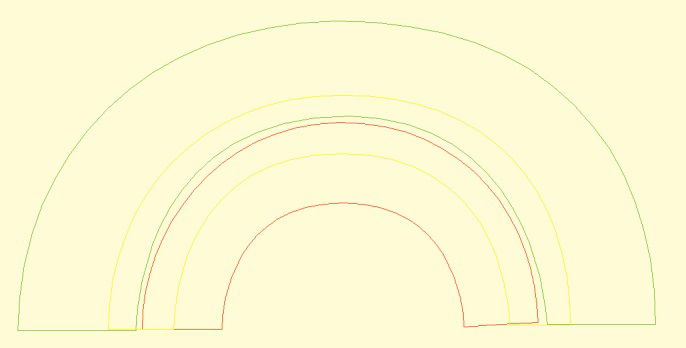

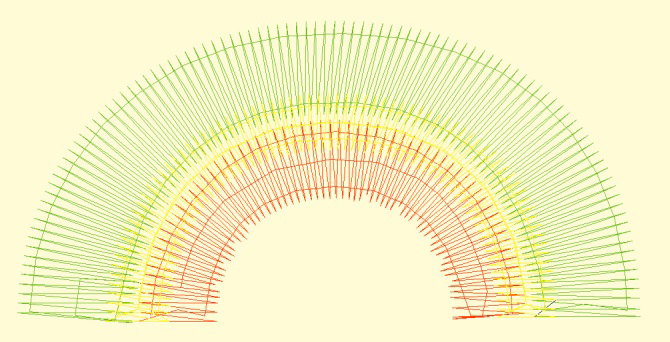

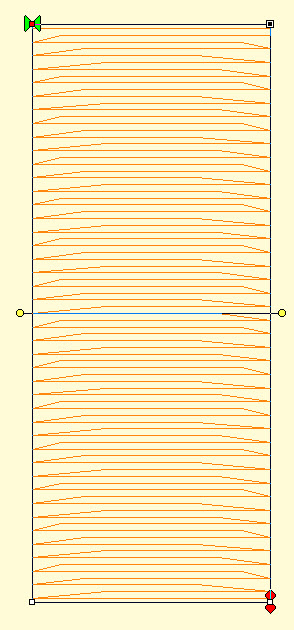

In the above image, notice that the inset of the darker-colored run is greater at the sides, and almost perfectly aligned at the top and bottom. This is because the fill will sew ‘narrower’ along the inclination – each line of stitching wants to pull the fabric in.

At the top or bottom, whichever stitches later, you may see the fill (or more typically a satin) ‘push’ or get ‘taller’ before the run happens.

2.) Adjacent filled areas pull away at the ends of the stitch lines.

When a line of stitching ends, be it from a fill or a satin, there is tension which pulls the fabric in the opposite direction of the line. This means that a fill or satin tends to sew ‘narrower’ than the object was drawn. We do use the compensation setting to help this – it makes the ends of the stitching a little bit farther out past the edge of the shape. It helps, but sometimes that’s not enough, especially where two fills or satin edges meet.

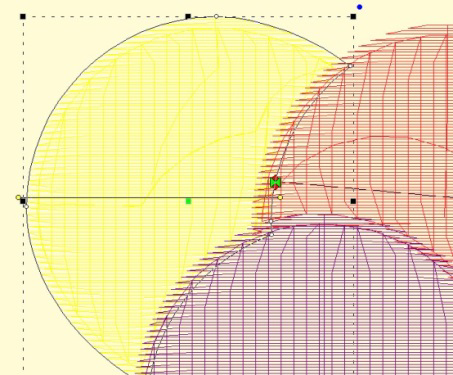

Solving this usually is done by overlapping the object shapes. The shapes can overlap quite a bit sometimes if there is compound registration from more than two objects all positioned at each others’ edges.

If there is an edge-run in each object, for underlay or travel purposes, sometimes you can use it as an ‘anchor’ for a subsequent object; move the outline so that it overlaps just to that edge-run and has some needle penetrations which grab it. This tends to balance the stress on the fabric between both adjacent objects.

In the image above, you can see the earlier yellow object has its outline inset ‘under’ the red and purple objects, which allows for a degree of freedom of movement while it is being sewn. The other objects will not overlap as much as it appears on screen.

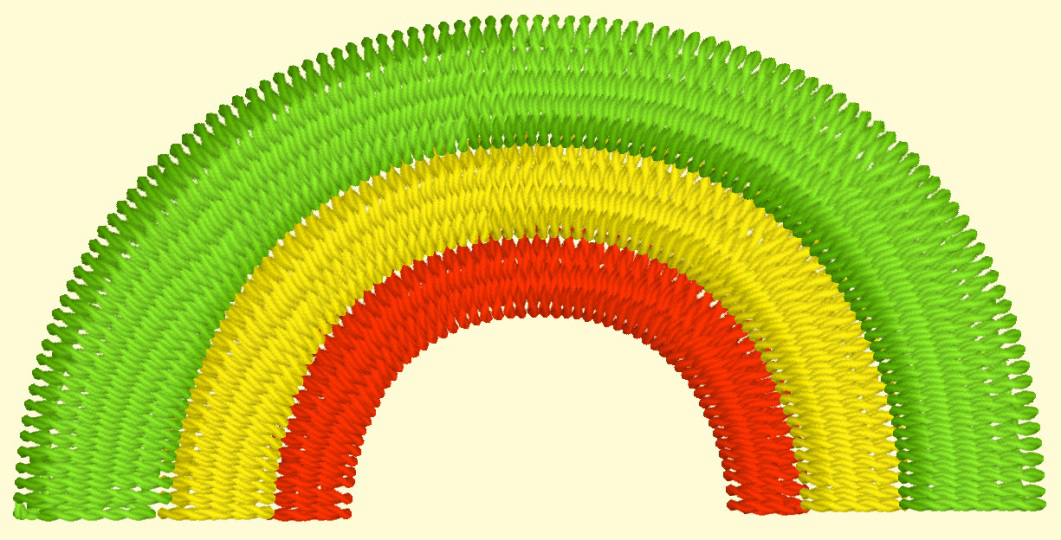

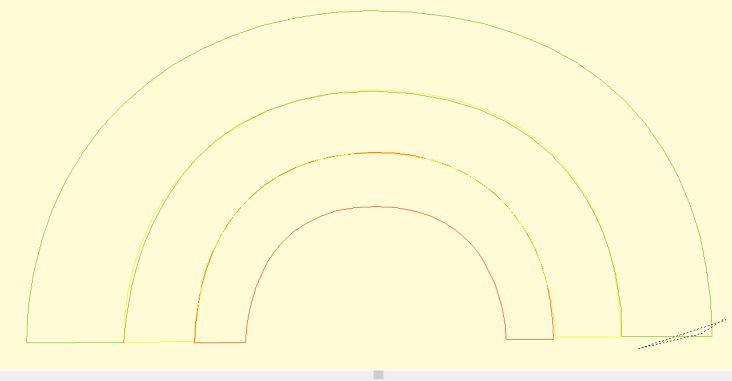

Oh, look, a rainbow, how nice! No. No, it isn’t. This is a perfect example of compound registration at work and you will not be able to sew this consistently.

The red, then yellow, then green sew in that order. It sounds right. But the gaps you see when you sew will make you wonder if you should take the machine in for repair. This will probably work better going outside-in with the green, then the red, then the yellow, and don’t be surprised to have the green and red objects nearly touch each other in the middle under the yellow.

Do not do it like this:

Rather, more like this:

Watching a child use a crayon to color an image will help you understand this quite clearly. If you move the crayon back and forth in one direction, the edges of what you are coloring will not have as much color as the center. Typically an older child will work the crayon along the edges at some point which will extend the color more evenly. The same is true for embroidery. Using multiple layers of stitching, with different directions, yields better coverage. It also divides up the shift in the fabric, which helps registration; instead of everything being pushed one way, it gets pushed half as much in two directions, and your stabilizer will be better able to support it.

This means that if you want more coverage, try making two passes or more, each with less density (instead of one pass at 4pt, try two at 8pt). This is in fact the reason for the underlay options in fills and satins.

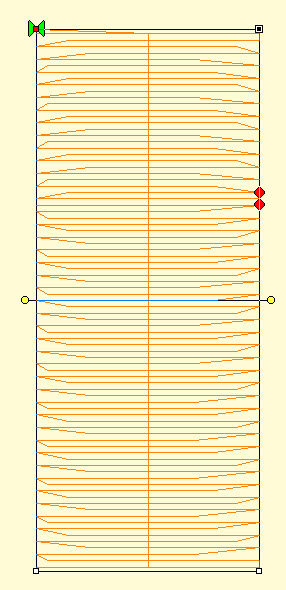

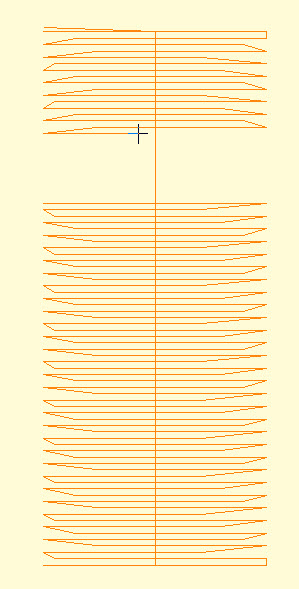

When doing a fill, often times you will want to position your Exit bead somewhere in the ‘middle’ of the shape. This means that the pattern will sew one part of the design, then go away and work its way back. If your fabric is being flattened by the thread, and you do not have undersewing for better coverage, this can leave what appears to be an ‘unstitched’ line across your fill. There are solutions for this – use more in the way of underlay, and/or move the exit bead to the opposite ‘end’ of the pattern. It is often better to ‘run’ to the next object after your fill than to have the fill exit in the middle.

Left: A fill with the Exit bead midway in the fill. This causes the stitching to go from one side, then the other as shown in the center image, which is shown using the sewing simulator (in this image it has sewn below, and is now working its way down from the top).

Right: Entry and Exit Beads are at opposite ends, which can help the fill provide a smoother coverage.

We see these often enough that they are worth mentioning here.

Thread loops on the bottom of the fabric

This is always caused by the TOP thread having no tension, or not being in the take-up lever. It sounds counter-intuitive, but it’s true, the bottom of the design is controlled by the top thread, not the bobbin.

Thread coming up

Usually this is a bobbin case tension too loose, or not having the bobbin thread in the tension at all. While it is possible that the top thread is getting hung up coming from the spool (very common actually) this usually happens in specific areas and appears quite severe. If you are seeing a lot of points coming up, it is usually the bobbin not having tension.

Machine-gun sound

It sounds silly, but yes, that rat-at-tap-tap can be annoying and even destructive to the machine. Usually this is your hoop flopping around when the needle rises out of the fabric. The needle lifts it up just a bit, then pops out, and the hoop flops down. It could mean the hoop is mounted wrong, is defective or simply a bad design. You can help by making sure you have a sharp needle, sized as small as you can for your thread. And you can try putting something on the arm of the machine to soften the blow. And definitely have it checked by a competent sewing machine service.