Product: StitchArtist™

StitchArtist is a program designed to allow embroiderers to create stitch designs from scratch using existing artwork or by ‘drawing with stitches.’ It has been described as an object-based digitizer. You draw and control the shapes, set the stitch type and properties, and StitchArtist generates stitches for you. When you want to create stitches, that’s what it does.

StitchArtist comes in levels which suit different skill level embroiderers.

Note: Each topic in this manual may have notes for different levels. This allows for continuity in the learning process. As you progress, you can purchase additional levels whenever you are ready.

Level 1 is designed for a hobby embroiderer who needs to be able to create stitches without going into debt or spending much computer time. Level 1 offers a limited set of stitch types and, more importantly, properties for those stitches, so that the user can simply ‘create.’ Typical projects for Level 1 are applique designs, running stitch designs and simple filled shapes, backgrounds or unifying elements for design compositions etc. It is not designed for logo work or publishing, unless you’re working with applique.

Level 2 includes Level 1 and is designed for basic skills training for those who would like to create more sophisticated designs, as well as a basic set of tools for logo creation. It will allow the user to learn a wide cross-section of stitch types and properties, and have enough freedom to create virtually anything.

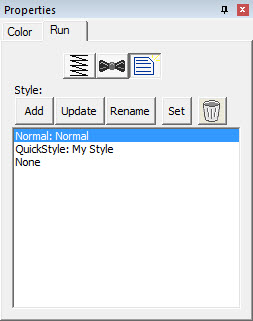

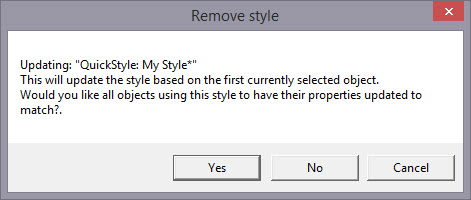

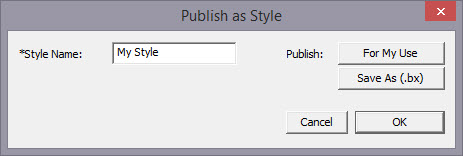

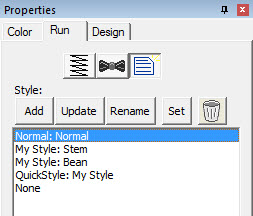

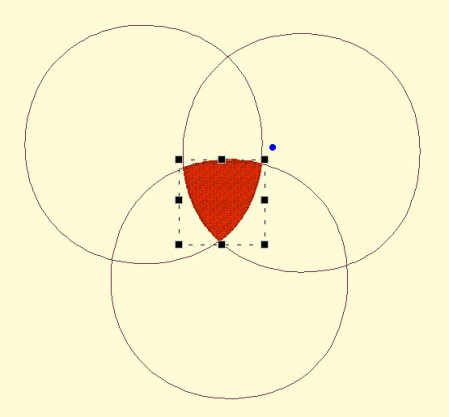

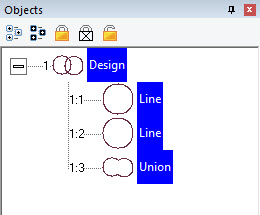

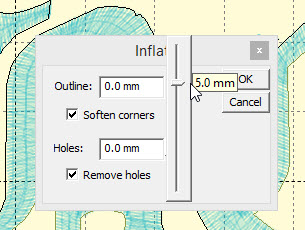

Level 3 includes Level 1 and Level 2 and is designed for someone who either loves to create designs or works commercially in the embroidery field. This level includes advanced items such as QuickStyles, adding user-created motifs and designs, graphical operators such as Reconstruct, Outline Stitches, Inflate, Cut, AND, Union and Break, extended Vector support and more.

Illustrations in this manual are shown with Level 3 enabled unless otherwise noted. Feature differences in other levels will be discussed in the text.

StitchArtist is not an attempt at fully automatic design creation. It will not attempt to ‘convert an image’ into embroidery; It does not contain photo-to-stitch for example. These are all reasonable tasks, but are not the same as what StitchArtist is.

It is also not a ‘customizing’ or ‘editing’ program for the manipulation of existing embroidery designs. You may load designs so that you can add stitches to them, but they are not alterable in most ways.

Embroidery designs have been created with computer programs since the late 1970’s. The hardware used by artists at the time came from the CAD/CAM industry (Computer Aided Design/Manufacturing) and consisted of a CAD “digitizing” board (like an architect desk) and a mouse-like ‘puck.’ As no one thought to change the CAD term, the word “digitizing” has been with us in the embroidery craft ever since. We prefer the term “Design Creation” though for two reasons: 1: Because it really is more accurate. And 2: Because the term “digitizing” carries negative connotations of difficult-to-learn software. Therefore “Digitizing” and “Design Creation” are interchangeable in this manual; however our product is a change in the user interface, and is easier to use. Just wait, you’ll see.

Design creation is a two-fold learning process. First, there is the software. That is the set of buttons and sliders that make things that can be stitched. That’s pretty easy to learn, especially for anyone who understands drawing programs or even has general computer skills. Whereas digitizing software in the past had been developed in its own little world, and the graphics programs went their own ways, the two are now converging with similar tools and operations in both. Do not be misled into thinking that embroidery and graphics are at all similar though, as designers can get away with all kinds of things in graphics that are simply not possible in embroidery. The level of sophistication in an embroidery creation program is much higher than a graphics program, generally speaking.

That brings us to the second and more difficult part of the learning curve – the knowledge of embroidery itself. Embroidery involves thread and fabric. Both are by definition flexible, usually stretchy to some extent and operate differently in different combinations. In graphics you can do things however you want: In any order, at any place, or jump from point to point without regard. And the result will always look the same. With embroidery all those assumptions are false. You need to understand which stitches will go down first, and why they go there, and you need to really think about where the machine is going to go as it stitches the design. Generally there are three areas of thought that need to be part of your process when you create a design:

The material, thread and project combination. This dictates certain items such as the amount of coverage you need, the maximum number of stitches within an area that can be added to the fabric before it puckers, and how it will be stabilized so as to mitigate somewhat the inherent limits of the fabric.

The path the machine will take as it creates the design. You don’t want to leave thread trails all over, and you don’t want to have to cut those either. Even if the machine does that for you, you still have to spend the time on that process. And if a design always sews in a given direction, you wind up pushing the fabric around so much that the later stitches won’t align or ‘register’ with the earlier ones.

The types of stitches used. This is the topic that is easily understood, but can take a lifetime to master. The basic stitches are pretty obvious, but the quality of the output comes from clever usage and combinations of elements.

This manual covers the usage of the program itself, and attempts to interject some knowledge of the embroidery process as well. However, we very much recommend the reader take educational programs on design creation from others. There are a number of wonderful educators for digitizing in the marketplace, and their fees are generally well worth the knowledge you will gain. With respect to those instructors, please humbly accept that any differences you find herein with regards to your teachings, are not intended to be the ‘only way’ someone ought to do something, nor necessarily the ‘best’ approach, but perhaps is what we ourselves are comfortable teaching. We all have our own styles, and those differ from time to time.

If you have never embroidered before, take some time to learn the use of your machine and the basics of embroidery. Your local sewing machine store will have classes that you can attend to help you get going. We must assume for the purposes of this manual that you understand the ordinary hobby aspects of embroidery – what a hoop is, what stabilizer is, what a ‘design’ is etc. Hopefully you have at least stitched something successfully.

You do not have to be an artist. Really -- let’s say it again --you do not have to be an artist.

The reason is that embroidery creation is more of a ‘color-by-numbers’ process. You may be an artist, and that’s great. You can even create your art within the program. However the process of laying stitches on top of your art or image is a mechanical, methodical and logical process, provided that the art is suitable for embroidery. And there too is a reason why we ask that you have at least done embroidery – it will provide you some insight as to what’s possible with embroidery, and what simply isn’t. Naturally an artist can alter a complex image to be more suitable for embroidery, and a person with some experience creating designs may be able to do that intuitively as they work. It all comes from the learning process and involves much trial and error along the way. You won’t learn to paint overnight, nor learn to play Chopin the first time you sit at a piano, so please don’t expect to be creating complex designs well the first time either. But with a bit of persistence, creating designs is a much faster and easier learning curve than those other endeavors. And you can begin with simple things and start sewing in practically no time.

Reminder about Levels: Illustrations in this manual are shown with Level 3 enabled unless otherwise noted. Feature differences in other levels will be discussed in the text. Some sections have information pertaining to multiple levels. We have indicated the minimum level for which the text is relevant. Where practical, we have added higher-level information toward the ends of sections.

The interface in

StitchArtist is different in some respects than programs that have come before,

especially digitizing software. We’ll define all these terms as we go, but if

you’re familiar with them already there are some things you should know now…

The interface in

StitchArtist is different in some respects than programs that have come before,

especially digitizing software. We’ll define all these terms as we go, but if

you’re familiar with them already there are some things you should know now…

When creating embroidery, you will be normally doing several types of tasks:

1. Loading artwork as the basis for the design

2. Creating stitch-generating “objects.”

3. Editing the “shapes” or “outlines” of those objects.

4. Editing the “properties” for those objects.

5. Moving objects around on the design page.

6. Sequencing objects for sewing order.

7. Adjusting the “entry and exit points” for sewing objects.

8. Colorizing objects.

In StitchArtist these different types of operations do not require any program ‘modes’. Generally speaking there are only two modes that you’ll run into during design creation: The normal ‘Selection’ mode when the program starts, and the ‘Creation’ mode that you’ll use while creating the designs.

You will not need a separate tool to reshape the outline of designs, nor need to switch modes to size or move objects. All the tools for design creation are accessed from either the ‘Create’ menu or the ‘Create’ Tool Pane, which is shown using the ‘Create’ button on the main toolbar.

All selected objects have their properties adjustable at all times, and the properties can be set on any number of selected objects simultaneously, causing immediate generation of the selected objects.

There are also virtually no “Apply” buttons or ‘Enter’-key requirements – stitch generation is automatic and immediate.

There are a number of features in the platform that are consistent across the products including the Navigation HUD (a compass rose in the top, right corner of the Main Window), the Zoom Slider, the Edit Menu, Zoom keys, etc. Please review these areas in the program help so that you’ll know the basic navigation of the program.

Objects are usually shapes that have stitch types and properties associated with them. The object may for instance be a Run, or a Satin Column or perhaps a Fill.

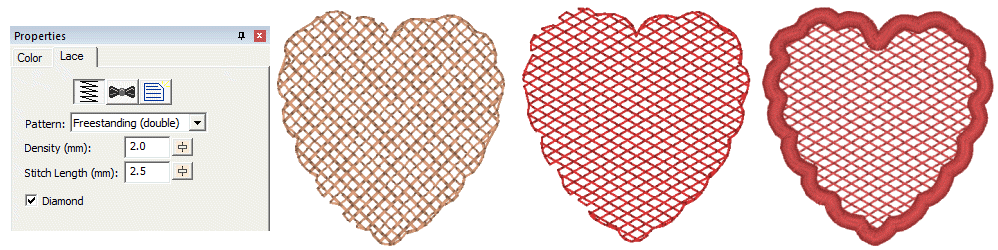

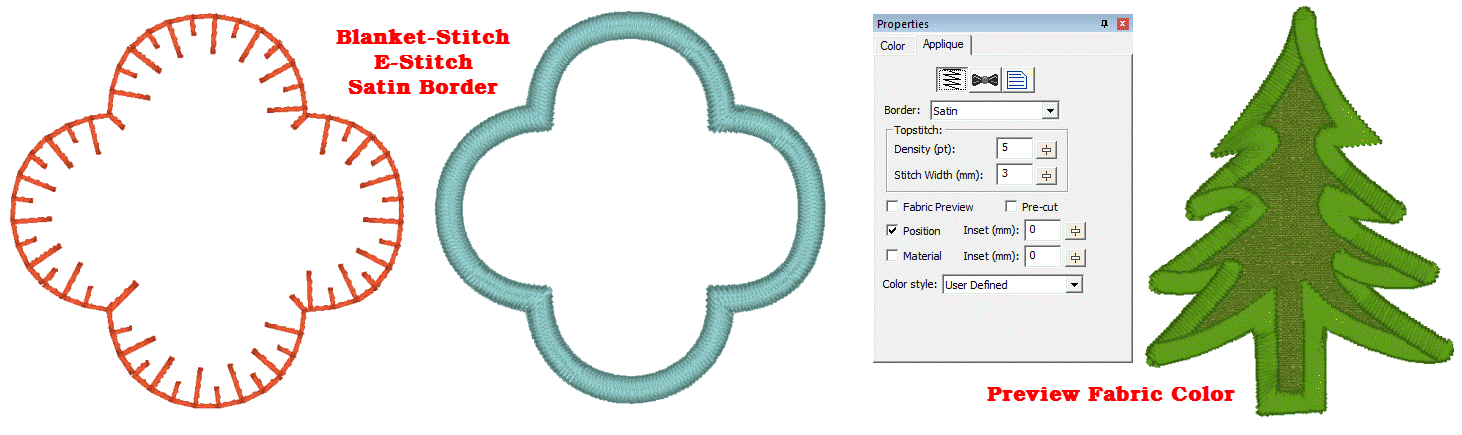

Objects can contain lots

of information: Outlines, holes, inclinations, breaks, images, stitches and

colors. Thus a single object could contain an applique – the shape of the

applique, a picture you want to print cropped in the outline, the stitches that

are generated to sew the applique and the colors for the position, material and

topstitch sewing, and even more. We’ll discuss all that separately, so please

keep reading.

Objects can contain lots

of information: Outlines, holes, inclinations, breaks, images, stitches and

colors. Thus a single object could contain an applique – the shape of the

applique, a picture you want to print cropped in the outline, the stitches that

are generated to sew the applique and the colors for the position, material and

topstitch sewing, and even more. We’ll discuss all that separately, so please

keep reading.

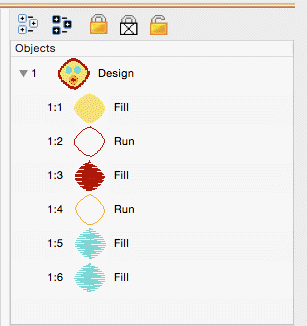

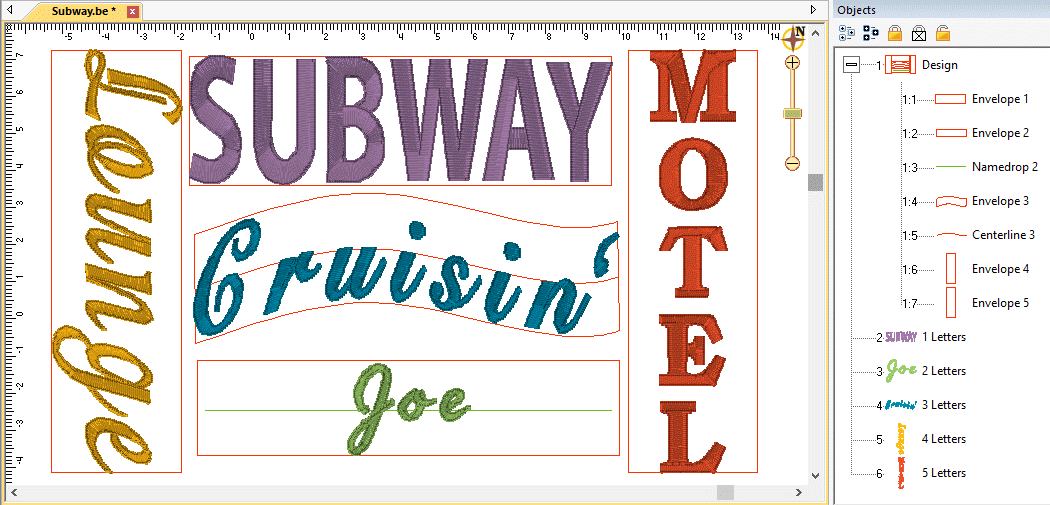

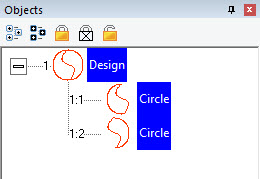

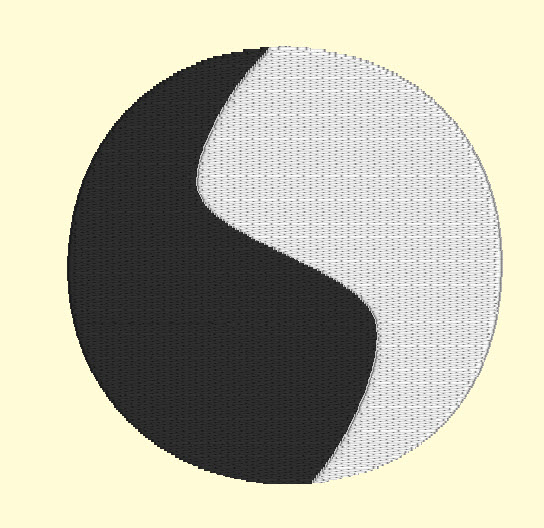

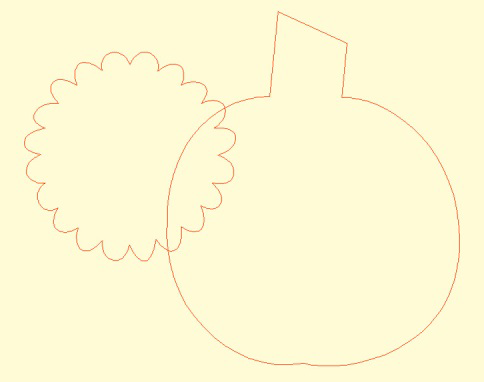

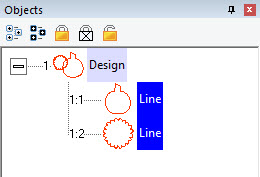

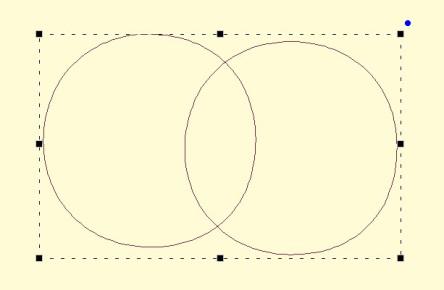

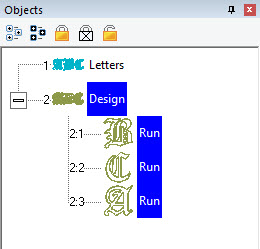

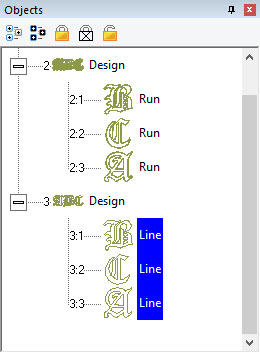

Designs are groups of objects that are collected together. This might be an individual design that you want to sell, or a smaller piece that you’ll reuse as an element in other designs. Designs let the user work within a section of an overall composition without being encumbered by the whole. This is similar, but not equivalent to, a term used in some graphics programs as a “layer.”

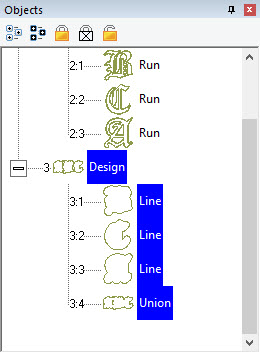

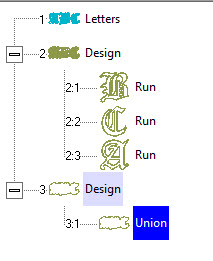

When observing the relationships between designs and objects, see that the Object View, normally docked on the right of the program screen, has at its ‘root’ level the designs, and when you expand a design, you’ll see the individual objects that compose that design. If you select a design, by clicking on it in the Object View, you will be selecting all the objects contained in that design as well. If you select all the objects in a design, selection of the design itself is optional. This is useful for copy/paste operations.

When creating new objects, you have the ability to choose where they go – into which design, and even where in that design they are created. We’ll talk more about that in the ‘Creating Objects’ section.

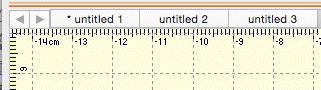

The top level of the program uses what is called a Design Page, which is related to a document or file. The Design Page is stored as a .BE file on your computer, and can contain any number of designs, each composed of any number of objects. You can have as many open Design Pages (or documents) as you like, and each is represented by a tab at the top of the main view.

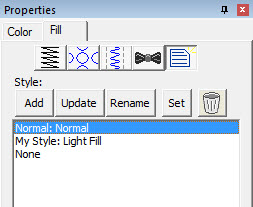

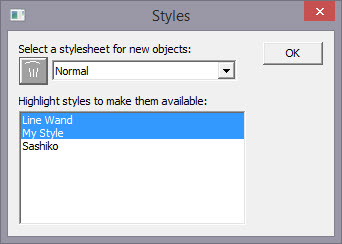

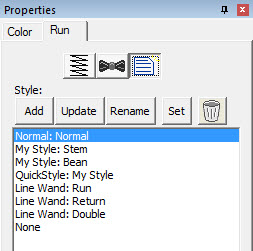

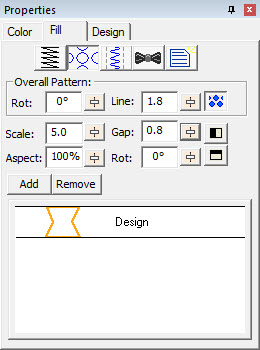

The interface has a Property Page, usually visible on the lower right part of the program window. The size of the Property Page can be adjusted using the splitter bar that lies at the bottom of the Object View. You can also drag the splitter bar that lies on the right of the Main View if desired. For general interface adjustments, please review the user interface section of the program help.

When you select objects their properties are shown as tabs in the Property View. If you have more than one object of a given type, the properties of the first selected object of that type are shown.

The controls for the properties mostly exist in five forms:

1. A set of buttons which let you choose which properties you are adjusting.

2. A drop-list which lets you select from a set up options.

3. An editable text field which lets you adjust a value.

4. A pop-up slider which lets you set an adjacent text field by dragging its value.

5. A check box which lets you turn a property on or off.

If you adjust a property, all the selected objects of that type will have that specific, and only that one, property adjusted. Having adjusted the property, the stitches will generate automatically. You should see the change in the stitches of the object immediately.

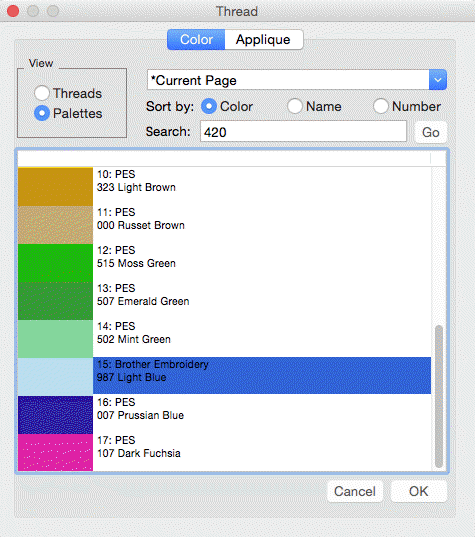

Color is a property of an object. Objects have one color each, except for appliques, which by definition need to stop the machine. When exporting stitches, objects of the same color that follow each other will not cause the embroidery machine to stop unless there are applique steps involved.

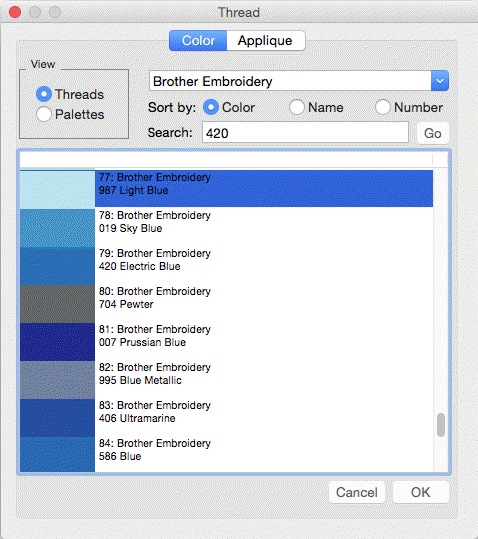

When no objects are selected, all of the colors for the page are visible and changeable. To change a color, simply click on it in the list.

.

.

Design creators often need to utilize a palette of given colors. Sometimes these represent a customer’s job requirements, and other times it is merely a matter of needle assignment for the embroidery machine. You can create palettes at any time using the menu Utility->Threads… And you can choose to use any palette as you adjust the color properties.

You can also create a palette on the fly while creating your design. If you wish to switch to an already-used color on the current page, select the ‘Palettes’ button in the color window and you will see in the list, “*Current Page.”

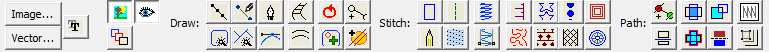

The tool pane is located

below the main toolbar. When you click the toolbar button to create stitches,

you’ll see this tool pane which is divided into sections.

The tool pane is located

below the main toolbar. When you click the toolbar button to create stitches,

you’ll see this tool pane which is divided into sections.

The first section is used to bring existing images or artwork into the program. You can load a raster image (Bitmap, Jpeg) or a Vector image (Metafile, Adobe Illustrator) or even use a TrueType font as artwork for your creation.

The next section contains view and mode options. You can hide the background images or the stitches while you are creating your designs. You can also re-sequence the objects in a mode that lets you click on them one after the other on the Main View.

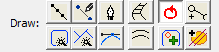

The drawing tools are next. These let you create shapes, open and close outlines, add inclination and carving lines, etc.

The Stitches section is used to apply stitch types to selected objects.

The Paths section is used by illustrators to convert images into useable embroidery shapes.

When using tools such as the Magic Wand, another section becomes visible as needed to allow for adjustments to the current process.

Sometimes you want to pan the screen – in other words, move it around – while not changing your zoom, or using the scroll bars. The easy way to do this is with the spacebar key. Hold the spacebar down, your mouse cursor will change to an image of a hand, and then you can drag the screen with your mouse.

While drawing shapes or dragging during edits, it is quite common that you will need to move to part of the image that’s not on the screen. Rather than use the scroll bars, which you can, you can also move the mouse to the edge of the main window. When you get within a few pixels of the edge, the view will scroll for you in the direction of the edge your mouse is over. When not dragging, the screen will not scroll automatically.

Sometimes you want a reference line that is not on the main grid. Place your mouse inside the area of either ruler – horizontal or vertical at the top or right edge of the Main View. Then, drag, using the left mouse button and you will then be setting an guide line. You can drag these guide lines wherever you like, and if you drag one back to the ruler area from which it came, it will be removed from the page.

Sometimes the view of the

artwork makes it hard to see what stitches you have created. You can quickly

toggle the images on and off using the Image Toggle button on the tool pane or

using the ‘b’ key.

Sometimes the view of the

artwork makes it hard to see what stitches you have created. You can quickly

toggle the images on and off using the Image Toggle button on the tool pane or

using the ‘b’ key.

The stitches generated are usually kept in view so that you can see what they are doing. However, sometimes you want to see only the outlines, and hide the stitches. This is done with the ‘Stitch View’ toggle button on the tool pane or with the ‘n’ key. This is helpful especially when editing.

Note: Stitches are not in view while drawing or scrolling.

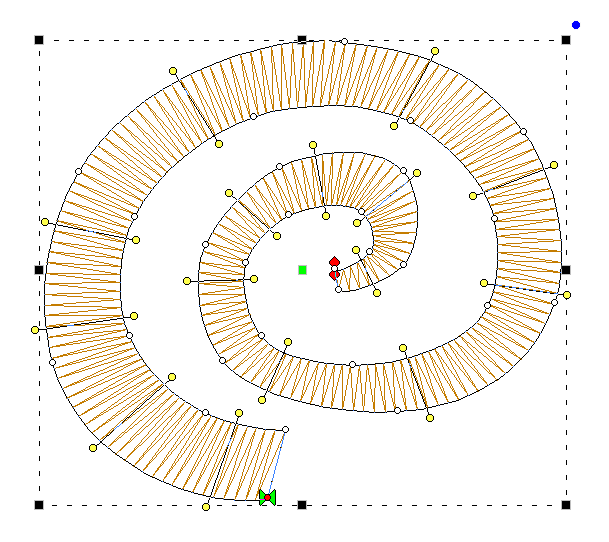

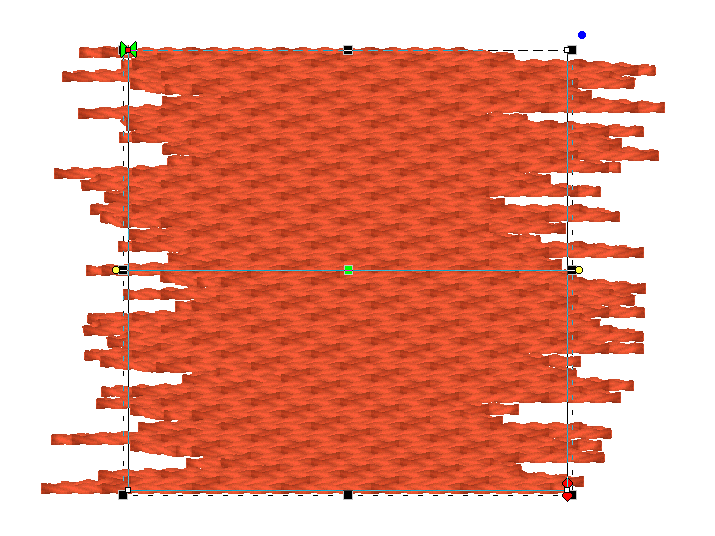

The Continuous View is used to

see how items will connect when embroidered in a continuous hoop, or as a

repeated pattern. It creates a set of duplicate images which let you see how

your design will connect or interact with an identical copy. The image is not an

actual design – it is just an image for reference.

The Continuous View is used to

see how items will connect when embroidered in a continuous hoop, or as a

repeated pattern. It creates a set of duplicate images which let you see how

your design will connect or interact with an identical copy. The image is not an

actual design – it is just an image for reference.

The offset setting allows you to inset a repeated element, instead of the default, 0, which aligns the image of the copy with the outer edge of the design.

In his book, Digitizing Made Easy, author John Deer writes about getting used to a particular scale or scales while you are creating a design. This allows you to learn what a useful distance in the real world will look like on-screen. The Embrilliance platform has a Preference which lets you calibrate the display to a Real Scale (See the program help on User Interface for details). Once you have done that for your computer/monitor setup, it does not need to be done again.

To get to a particular ‘zoom’ level, use the number keys. ‘1’ is a 1:1 ratio of the size of things on-screen to the real world. 3:1 and 6:1 are popular as well. If you use the number key ‘0’ you will be zoomed to your hoop.

Using a consistent set of scales is useful. Once you become well used to seeing design work at those scales, you’ll be able to know what the stitches will look like without having to sew them out. If you are zoomed too far in, you will likely be creating more detail than the design will need which slows the design creation process and can even negatively impact the sew-ability of the design.

If you are editing a design, feel free to use the zoom slider or other keys such as ‘A’ (All), ‘S’ (Selected) to work at a comfortable level. Generally speaking, unless an object outline is very large, you should be able to see the whole object on your screen while editing. Zooming in extra close can be useful to make the nodes perfectly line-up, but that is not necessary for a great design.

Note: If you have any objects selected, using the “s” key is a quick way to center the Main View on them for editing.

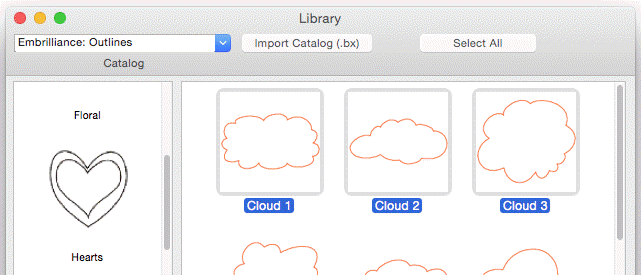

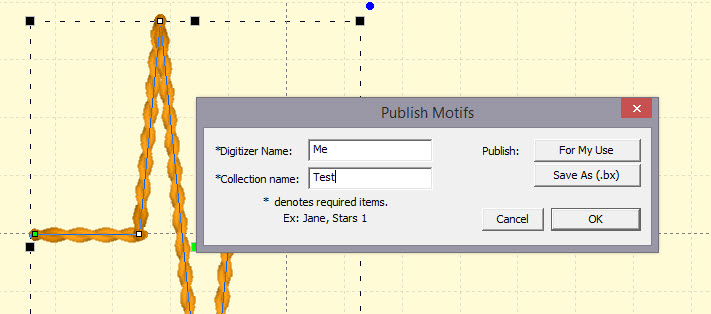

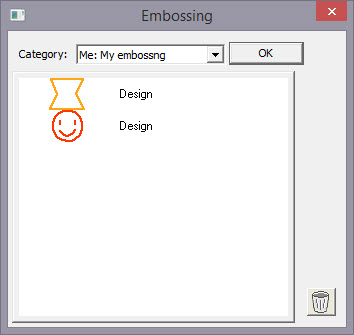

The Library button on the

main toolbar will bring in design collections that have been published in the

platform. There are several collections included which allow you to use them in

your own work – saving you time in drawing these shapes. When bringing in a

library shape, the program uses the current page’s view center and zoom level to

determine where it will come in. Once it has been brought in, you can size and

place it as needed, even edit its outline, as if you had drawn it yourself.

The Library button on the

main toolbar will bring in design collections that have been published in the

platform. There are several collections included which allow you to use them in

your own work – saving you time in drawing these shapes. When bringing in a

library shape, the program uses the current page’s view center and zoom level to

determine where it will come in. Once it has been brought in, you can size and

place it as needed, even edit its outline, as if you had drawn it yourself.

The Library has been extended to include hundreds of outlines that you can use with StitchArtist to make your own designs. They are even royalty-free!

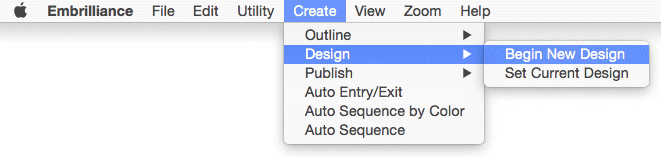

Designs and objects will create themselves as you begin drawing and as a result of copy/paste operations. But there are some options you should be aware of.

Each design page, which is represented by a working file (.BE) is selected using the tabs at the top of the main window. Each page can contain any number of designs. Sometimes it is useful to break up your work into discreet areas that can be managed as a unit. Designs are the mechanism for this. For example, suppose you make a nice rose. Now you want a bouquet. You could make the rose as a single design, and then place it in multiple positions and sizes to complete your image.

If you have no designs on the page, one will be created for you when you either bring in artwork or begin to draw. However if you wish to switch to a new design to begin drawing a separate piece, you use the menu Create->Design->Begin New Design.

If you are working back and forth between multiple designs, when you draw new objects you will need to decide where they go. To do this you have options:

1. Select the design in the Object View, and then use the menu Create->Design->Set Current Design.

2. Select an object in whichever design you wish to work, and begin drawing. Your new object will appear in the sequence following the object that was selected.

In computer graphics there a two basic ways to create an image and those are called “bitmap” and “vector.”

There are buttons to

allow you to bring in artwork from files. To use an image file such as a .bmp or

.jpeg as a backdrop for your design, click the “Image…” button.

There are buttons to

allow you to bring in artwork from files. To use an image file such as a .bmp or

.jpeg as a backdrop for your design, click the “Image…” button.

Once you have selected an image, the program will automatically begin a design for you (if you haven’t already), and place that image as a new object in the design. The image is selected and can be scaled or rotated, squished, etc. The images used for backgrounds generally are preferred to be semi-transparent, and that is also set for you. You can do whatever you like with the image at this point to help you begin creating stitch objects on top of it.

Once you begin making other objects, the image itself will lock into place. This means you will not be able to accidentally select or move it while you are creating your design. You can still edit it by selecting it in the Object View. There, you can even unlock it. Generally, once a stitch object has been placed over an image, you don’t want it moving around.

Note: The Image button works for pixel-based images such as photos and scans. Files created using vectors are not pixel-based images, and do not load using this function. See the section on Vectors for information about loading those.

Bitmaps are also known as “raster” images, which might be more technically correct but the terms today are used interchangeably. Bitmap images are composed of different colored dots. Images such as photographs fit into this category. Bitmap representations of art are the preferred type to create stitches from; they come in as background images over which you will create stitch objects.

When using a bitmap image, there is the issue of “resolution” which refers to how many dots called “pixels” are being used. The more pixels, the better the clarity of the image and fewer pixels make for an image that has little stair-steps in it when you zoom in. One might think that more pixels are better. However the program has to do a lot of work while you are drawing your design and an image with a lot of pixels makes it take that much longer to do each step while you are working. So it makes sense to use an image that is not super-duper-hi-resolution.

When deciding what resolution you want to use, or how many pixels should be in the image, it is worth considering how that will match up to the embroidery design itself. In an embroidery design the most common density of a stitch is about 0.4mm or 4 stitch points. This equates to a resolution of 64 DPI (Dots Per Inch) and that means that a typical 4” (100mm) square design would only need an image of 250 pixels on each edge. The normal smartphone will give you thousands of pixels on an edge, so any photo today probably has more than enough resolution for what you need.

We recommend, for simplicity, that you keep your image to around 1000 pixels on either edge. You can go for more if you’re making a super large design, naturally, but otherwise this is a good number. A lot of graphics that exist on the internet are 1024x768 or 800x600 because these are common web sizes. And those images have plenty of resolution for you to create embroidery. If you are making a 14” design, you might want to bump that to 1500-2000 pixels on the widest edge. But remember more is not always better.

Vector files are artwork

themselves. These files are brought in as objects. The user must realize that

graphics files contain objects with outline weights (thickness) and all sorts of

color properties that are inapplicable to an embroidery design. As such, when

importing vectors, the outline and its color are all that are brought in. For

some designs, this saves the user the work of having to re-draw the image.

Vector files are artwork

themselves. These files are brought in as objects. The user must realize that

graphics files contain objects with outline weights (thickness) and all sorts of

color properties that are inapplicable to an embroidery design. As such, when

importing vectors, the outline and its color are all that are brought in. For

some designs, this saves the user the work of having to re-draw the image.

Vector images are outlines filled with color – think of a company logo, cartoon, comic or coloring book.

As vector images already have outlines in them, and embroidery objects have outlines too, it might seem reasonable that starting with a vector-based image is better for this purpose. You would have little to draw because the art is already there for you. Simply set the stitch properties and you’re done, right? Well, you can, and we do import them for that purpose, but…

…In actuality that is rarely the case.

Vector artists can do things with their objects, such as ‘overlapping,’ which makes embroidery of the outline completely impossible. Also the shapes can be directly adjacent, which will leave gaps in embroidery. And vector artists jump from color to color and back again very casually. You don’t want to attempt this with embroidery. So, while the allure of using vector files is there, it actually can take more work to make a vector-based image work for you than simply creating objects over top of a bitmap image.

Another common problem using vector based images is that of the original source. There are a lot of clipart companies in the world, and they offer their product in a variety of file formats. When an artist submits an image that was created as a bitmap, the company then uses a program to ‘auto-trace’ the outlines in the image so that you, the customer, can get your ‘vector’ version of it as an EMF or WMF or AI file, etc. Those files are almost universally the worst thing to use for the reason that they contain as many as one hundred times the number of outline nodes as needed, and they are often ‘line’ nodes which means the stitches that will be generated will have to stop at each node.

Given these inherent difficulties, Level 3 has added features that let you overcome these problems.

However, for all these reasons we suggest you always use a bitmap picture - .bmp, .jpeg, etc. That is unless you yourself are the artist or whoever is creating the vector files as the original format and have done so with embroidery design in mind.

TrueType fonts exist as

single-color outlines in your computer. As many logos began life as a TrueType

font, you may want to use one as the basis for your design. There are many

free-to-use fonts available on the internet, although some require payment if

you use them. Check the font’s license to be sure, especially in commercial

circumstances. For this purpose, let’s assume you have either permission or

freely licensed fonts.

TrueType fonts exist as

single-color outlines in your computer. As many logos began life as a TrueType

font, you may want to use one as the basis for your design. There are many

free-to-use fonts available on the internet, although some require payment if

you use them. Check the font’s license to be sure, especially in commercial

circumstances. For this purpose, let’s assume you have either permission or

freely licensed fonts.

When you select text in a given font, the computer provides that in outline form. Each outline is given as an object. For example the lower-case letter ‘i’ will usually have two objects; one for the dot and one for the stroke. You can use these outlines as stitch types anyway you want. You can make them outline designs by applying a run, or you could use the art for satin stitches. You could even make them huge and set them to a fill, cross stitch or applique. It’s just a piece of art as if you had drawn it yourself.

You may use the drawing tools in the program to create your own art. There are enough tools there to do it, however, graphics packages will offer more flexibility in terms of things like pen nibs and gradient colors, but those are very different in embroidery when compared to graphics. Therefore the drawing tools in this program are geared toward stitch generation – you are literally drawing with stitch-generating shapes, making you a Stitch Artist.

As we explore the process of design creation, we need to get some terminology out of the way. If a word stumps you while reading halfway down a page, your brain will get stuck there and not retain anything else you’ve read. So let’s do some vocabulary, and at the same time, learn a few things.

Objects are the building blocks of the design. There are different types of objects, and their order or “sequence” is the order that the embroidery machine will sew them. Let’s look closer at what these really are.

Objects contain outlines, colors and stitch properties. As such we usually refer to the object by its stitch type, for example we may say it is a “Run object” or simply a “Run.”

When you have selected an object you may want to change its stitch type. You may at any time change any object from any stitch type to any other.

Some stitch types make use of the shape of the outline itself – for instance, the shape of a Run is where the run will be placed – along the outline. In contrast, a Fill would place stitches to cover the inside of the shape. When a stitch type is used that fills a shape, the outline will need to be “closed” and this happens automatically.

Objects have one stitch type. In StitchArtist, you are able to apply any stitch type on any object. Thus you could copy and paste an object and change its stitch type, thus having a ‘Fill’ and a ‘Satin Border’ around it. This allows you to adjust the outlines for each: In the real world of stitches on fabric, shape adjustment of the outline will need to happen in all but the most simplistic of designs.

When loading artwork for use as a backdrop for stitches, you may load as many images as you want. Each will be added to its own object. Ordinarily the first thing you would do when creating a design is to load the artwork, position it on the design page, perhaps select a destination hoop size, and then resize the image to that size. You can also rotate, stretch and mirror the image as needed. The image will display with a default transparency, which can be adjusted using the “Bitmap” property page for the image.

Once you begin creating stitch objects on top of that image, the image will “lock” automatically in place. This is the same as if you lock it using the Object View toolbar buttons. A locked object means that it cannot be selected by clicking on it in the main view, if it isn’t already selected. Any locked object can be selected using the Object View. So it is possible to move or alter the transparency of the image even after you have begun to add stitches, if you care to do so.

The platform is designed for the greatest flexibility in design creation. This is to suit amateurs and experienced users alike. But that flexibility requires some minimal explanation before you set off.

This is a chicken or the egg question. Any object may have its stitch type set to anything. And that can happen during drawing, or after drawing. What this means is that you can draw an outline, then assign it a stitch type. Or you can click a stitch type and then click a drawing mode to begin. There is a catch with this order of operation though – If an object is currently selected, and you click a stitch type, that selected object now becomes the new stitch type.

To clarify, if you want to begin a new object by setting its stitch type and then setting the input mode for drawing, make sure you don’t have anything selected first. Click on the design page background to have no objects selected.

Input Type First

If you prefer, you can select an input type, for example Point input mode, then select the type of object it will be, for instance a Fill. When you complete the outline, and the stitch type is set for Fill, the program knows that you will also want to draw an inclination line to set the angle, so it will automatically put you into that mode as soon as the outline is complete.

Some of you will prefer to first make your artwork as ‘Line’ objects with no stitches present, and then later set the stitch types. This is perfectly acceptable. Simply begin drawing. If there is an object selected, the new object type will switch to ‘Line’.

Often you will create a series of objects that are the same stitch type, for example: Run, Run, Run. In this case, after your first object, make sure to click off it so that it is not selected. When you start drawing the object type will be picked up from the previous object. Alternately you can type ‘q’ to begin drawing an object using the input method and stitch type of the last-drawn object.

The creation of objects is also likely to cover one or two object types, repeated, one after the other. For example: Run, Satin, Run, Satin, etc. Or, another example: Run, Double, Run, Double.

For this circumstance, you can quickly begin creation of an object with two hotkeys: ‘q’ and ‘w’. These let you begin creating an object using the exact method of the last object (‘q’), or the one prior to it (‘w’). These hotkeys will not only select the object stitch type, but also the input mode as well – you can begin drawing immediately. For more keyboard shortcut information, please see the Keyboard Shortcut section.

Normally when you begin to draw a new object, it will be placed at the end of the current design. If you wish it to be created in a specific place, select the object that will sew before the object you are about to draw, and then begin drawing your object. This is useful if you wish to go back through your design and create connective runs between segments, or if you simply forgot a piece.

Often you will have a lot of objects, and sometimes you’ll want to find a selected object in the Object View quickly. Select it in the Main view by clicking on it, and then use the context menu option, ‘Reveal in Object View’. This will work only for the first selected object, if multiple objects are selected. The Object View will scroll to position and expand the design containing the object.

Drawing is the main bit of work used to create a design. This section will let you know about various drawing methods.

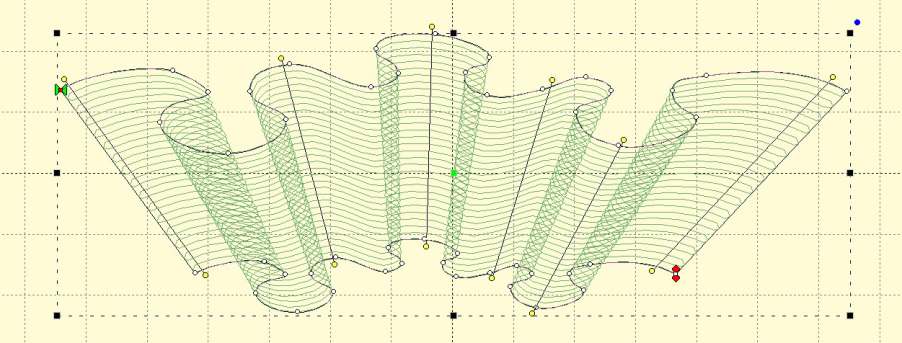

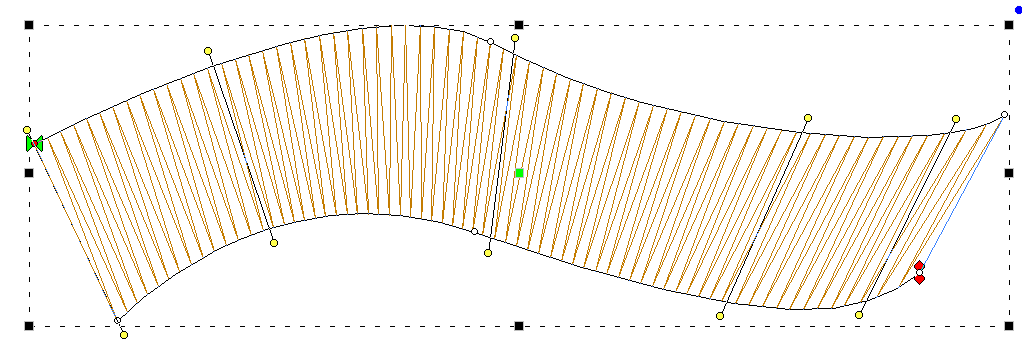

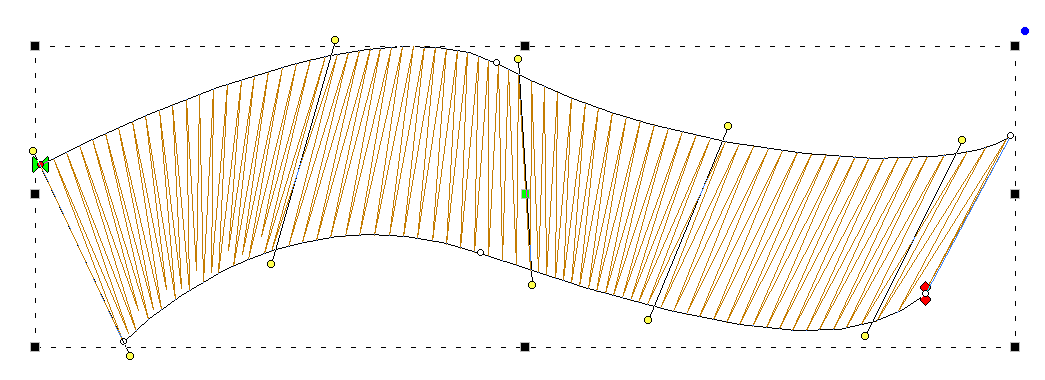

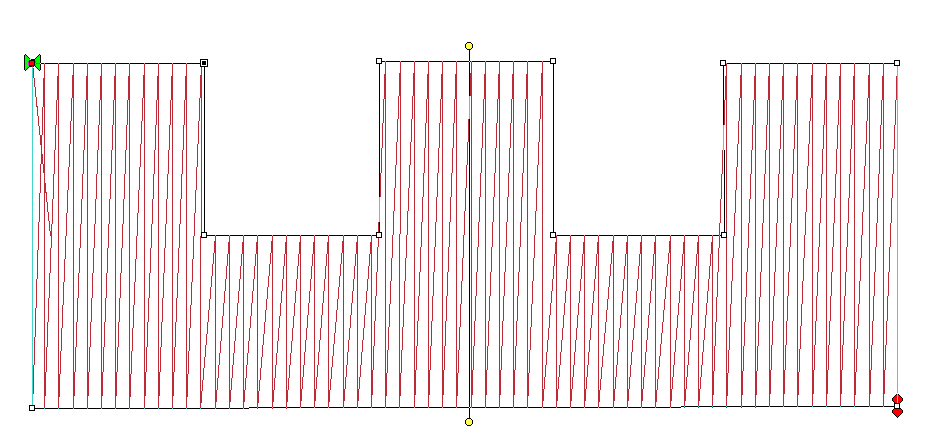

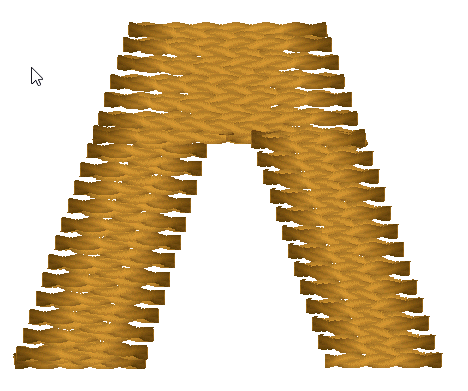

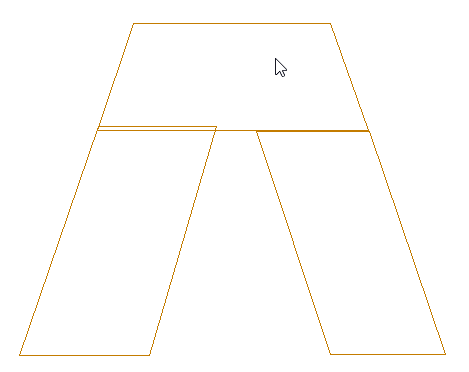

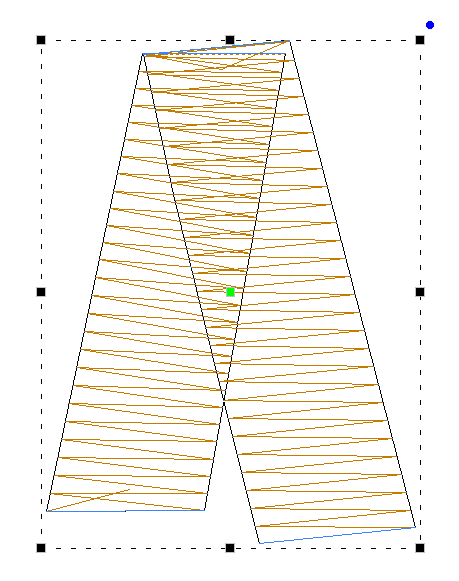

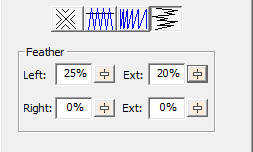

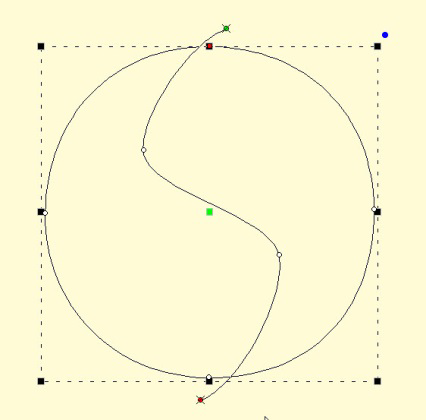

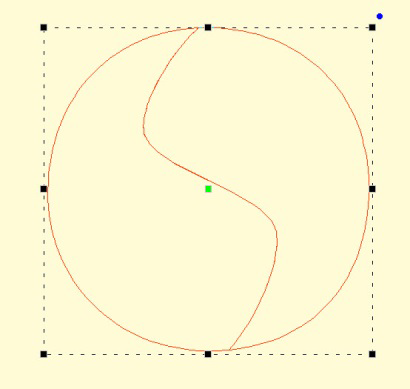

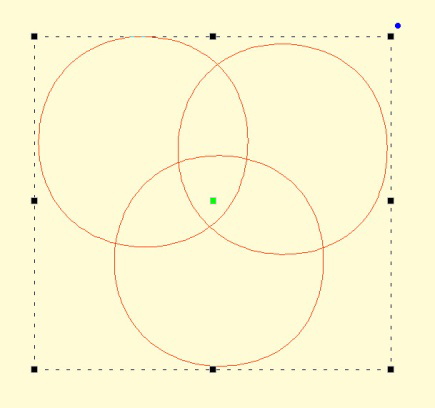

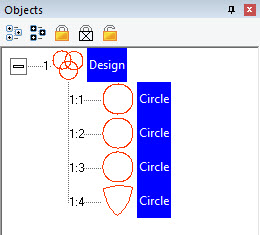

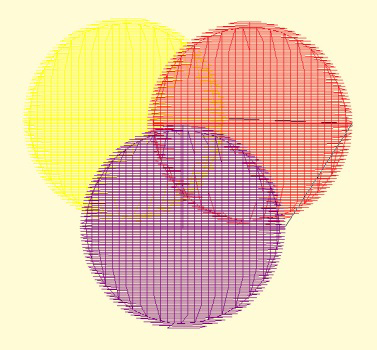

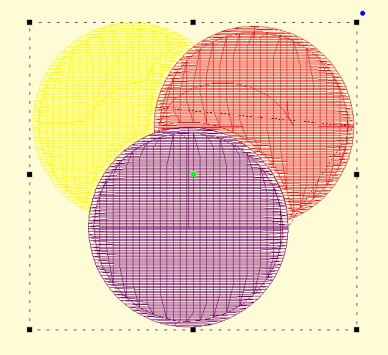

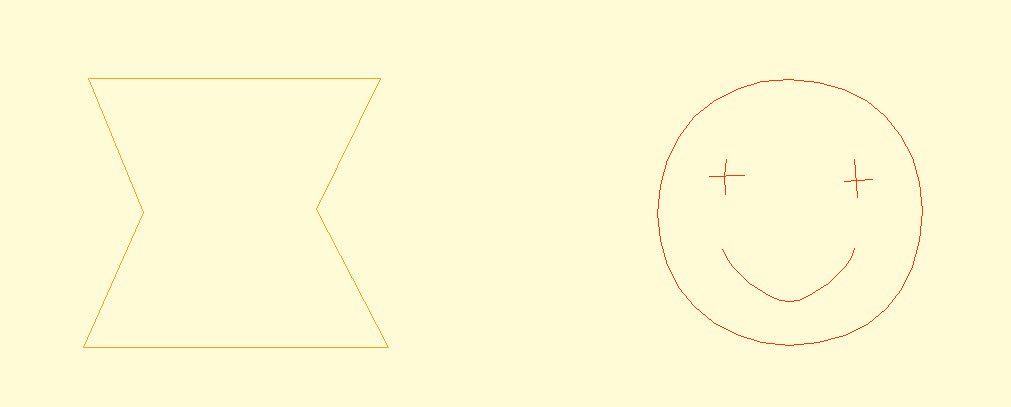

(Level 3

shown)

(Level 3

shown)

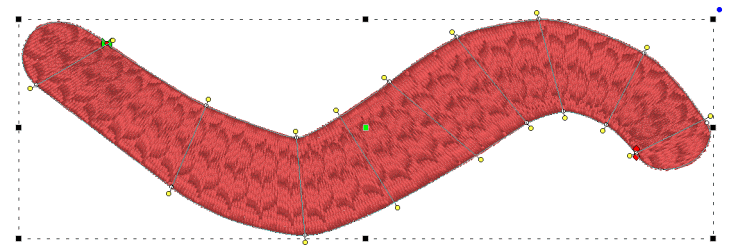

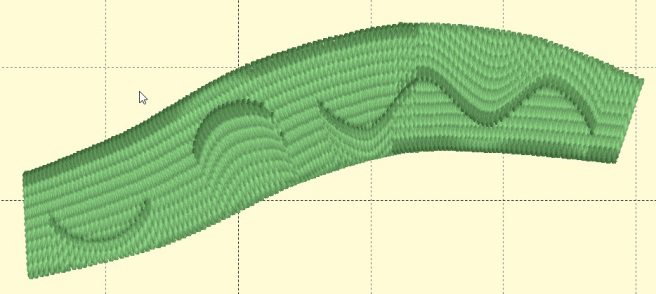

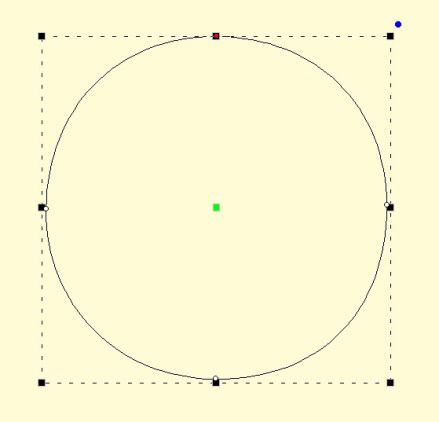

Objects are usually shapes called “outlines”. The outlines are created by you, the user, drawing on top of a piece of artwork, importing a piece of artwork called a “vector file” or with the assistance of a Magic Wand (if you prefer not to create the shape yourself). An object’s outline may also contain one or more “holes,” also interchangeably called “voids.”

Objects will usually contain stitching of a certain kind, for instance a satin-stitched column.

The outlines are shaped using points on the shape called “nodes.” There are different kinds of nodes, and there are many things you can do with nodes to change the shape of the object. When you click on a node, you are highlighting it and its appearance will change to show that highlighted state. When the program sees that you have highlighted a node (or nodes) it will change what it does with your input based on that fact. For example, using the ‘delete’ key on an object that has no nodes selected will delete that object. However if you have selected nodes, then the delete key will delete those selected nodes.

Note: You do not need to switch modes to reshape an outline. You click an outline node to highlight it. If you wish to work with the object as a whole, either ctrl-click the highlighted node, or click off the object and then back on it. When none of an object’s nodes are highlighted, you are able to move and re-size the object using the handles that appear.

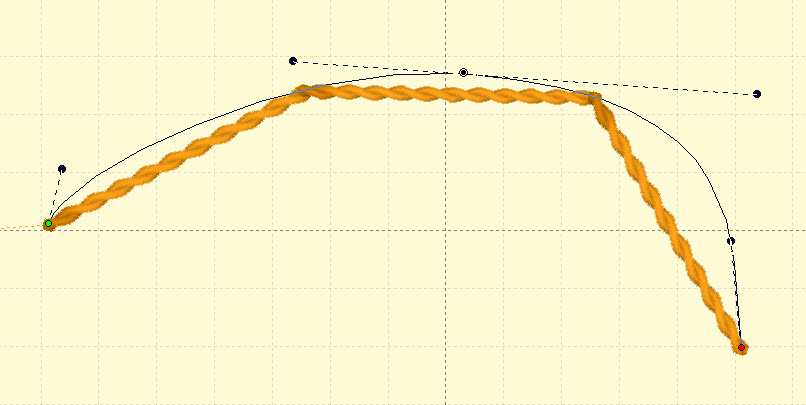

The underlying implementation of graphics in the platform uses Bezier curves, named after the man who first made use of them to design car bodies. Why do we use them here? Because the world has adopted these annoying-but-useful little curves; and all drawing packages, CAD packages and design software understands them, so there are a lot of people who have been trained in their use. Are there better solutions? Well, yes, but let’s not get into that right now, lest we upset the Math Police.

The idea of a Bezier curve is fairly simple. You have a start point and an end point, and a curved line that runs in between them. If you have a series of these, you can draw any kind of shape. The fun part is that the curve between the two endpoints is controlled by two ‘Handles,’ one connected to each node. In a simplified way, the first handle (which is connected to the start point) will determine how the line will curve as it takes off from the start. Likewise, the second handle will determine how the line comes in to the end point.

The benefit to embroiderers using these curves is scalability; Size does not matter. So if you make a Run stitch object using a curve, those stitches will generate nicely on that path at virtually any size, and the sewn result will be a nice clean curve even when made large.

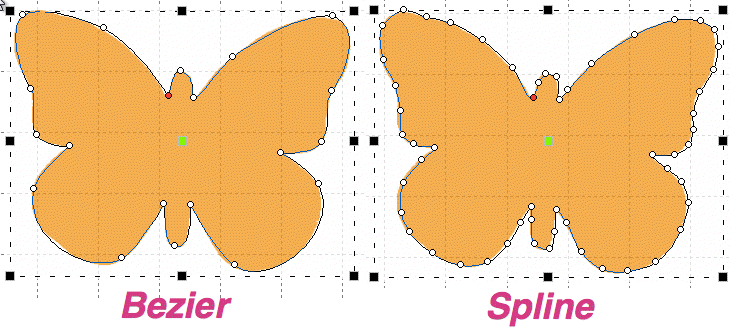

When creating and editing

outlines for shapes, you are always creating a Bezier form. For beginners who

are inexperienced with Bezier there exists an option to work without “handles,”

both when inputting a shape and when editing a shape. When the Bezier handles

are hidden on an object, you can edit the outline by moving, adding and deleting

nodes. This type of outline is known as a ‘spline’. The limitation is that you

cannot change the shape of the curve between outline points. That is where the

normal Bezier handles come in. You can switch any object at any time between

spline and Bezier, just be aware that when you go to spline, your edits between

nodes will be lost. Generally we always recommend that you learn the Bezier and

we have made every attempt to ease you into that.

When creating and editing

outlines for shapes, you are always creating a Bezier form. For beginners who

are inexperienced with Bezier there exists an option to work without “handles,”

both when inputting a shape and when editing a shape. When the Bezier handles

are hidden on an object, you can edit the outline by moving, adding and deleting

nodes. This type of outline is known as a ‘spline’. The limitation is that you

cannot change the shape of the curve between outline points. That is where the

normal Bezier handles come in. You can switch any object at any time between

spline and Bezier, just be aware that when you go to spline, your edits between

nodes will be lost. Generally we always recommend that you learn the Bezier and

we have made every attempt to ease you into that.

Note: If you want to quickly reshape a Bezier curve but don’t understand the handles, we have added a feature that lets you drag on the outline, between two nodes, and the outline will follow your mouse, adjusting the handles automatically. This is also very handy when you want to quickly draw with a very minimum of nodes, (very good for re-sizing later).

‘Nodes’ and ‘Knots’ mean the same thing as used here, and that is they refer to the outline points which are drawn and selectable.

Some things you can do with nodes on an outline:

• Select a node by clicking on it.

• Edit nodes by dragging them around.

• Add nodes by double-clicking where you want one to appear, and you can double-click a node to remove it.

• Drag around a set of nodes, in which case you will select all the ones in your “lasso”.

• Right-click while nodes are selected and change properties and do other things with the outline.

When a shape is drawn, it

goes from one node to another. It can either form a straight line to the next

node, or it can form a curve going ‘through’ that next node on its way to the

one that follows. The advantage of curves is that when you scale the design up

in size, the result is a nice smooth outline. If you draw with all ‘lines’, as

many have done in the past, you are severely restricting the useful size of the

outline you are creating. For this reason, we normally draw with curves, and you

can switch to a line as you enter points (for example by holding the ‘ctrl’ key)

or you can do it after the design is created.

When a shape is drawn, it

goes from one node to another. It can either form a straight line to the next

node, or it can form a curve going ‘through’ that next node on its way to the

one that follows. The advantage of curves is that when you scale the design up

in size, the result is a nice smooth outline. If you draw with all ‘lines’, as

many have done in the past, you are severely restricting the useful size of the

outline you are creating. For this reason, we normally draw with curves, and you

can switch to a line as you enter points (for example by holding the ‘ctrl’ key)

or you can do it after the design is created.

If you think about it, straight lines are not ‘natural’ except in math; only people create things in the real world with perfectly straight lines. So curves and cusps are very useful, unless of course you are making a geometric design.

Notes: ‘Curved’ and ‘Line’ node types refer to the path coming toward the node. The path leaving the node is controlled by the following node.

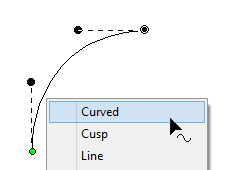

A ‘Cusp’ allows two curves to go in different directions away from a common node, whereas a ‘Curved’ node creates a smooth line through the node, transitioning between the two curves smoothly.

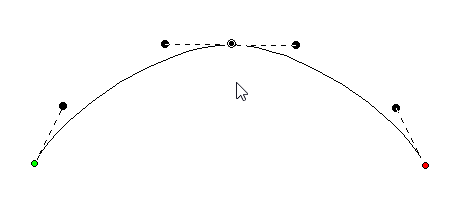

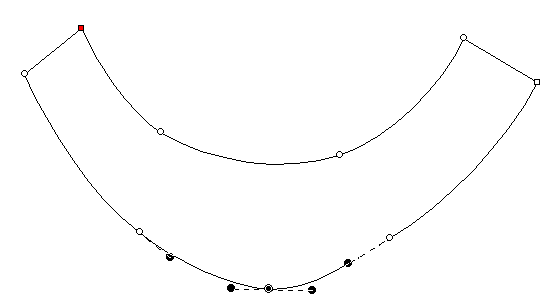

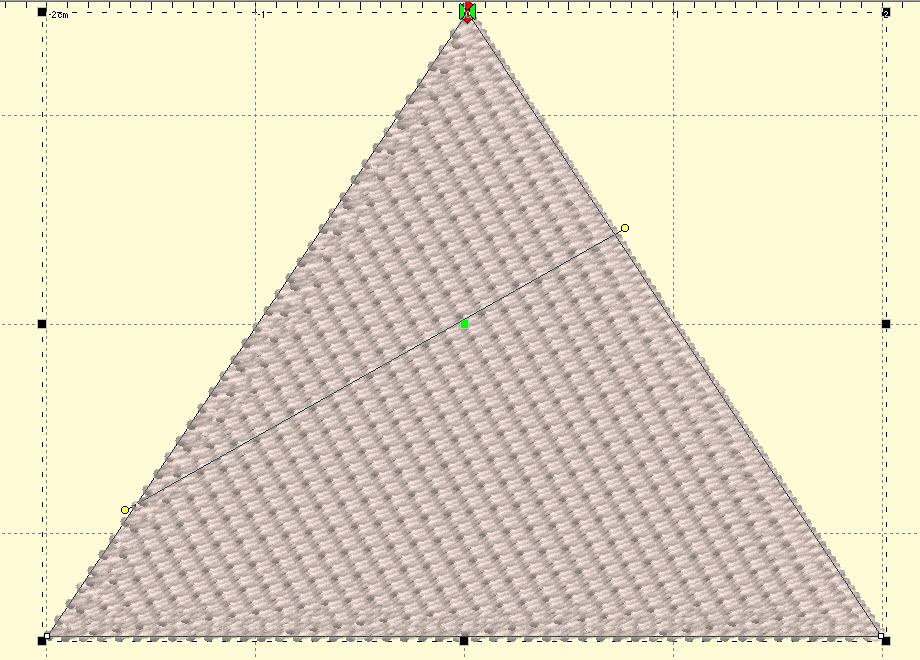

Here is an example of a curved node in the middle, and a hard point at the end. See how the path is a flat line going toward the final point. The path shape is defined by the node it is going toward.

A straight line will not have handles. There is no need, as there is nothing to adjust. If you want to make it curve, change the node type.

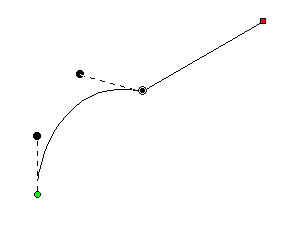

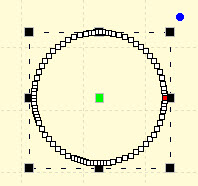

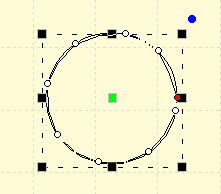

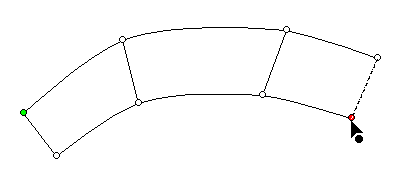

On any path, there is a green node that indicates the start, and a red node that indicates the end of the path. A closed shape will naturally have the end positioned over the start, so it appears red.

If there are only two nodes in a path, you have a section. The section can be a line or a curve, depending on the later node type. If you add a third node at the end, and that one is also a curve, now you have a choice as to what to do with the curve as it passes through the middle node. It can be smooth-flowing, in which case the curve looks like one continuous line. Or, it can be disjointed, making two distinct curves, in which case it is called a ‘Cusp’.

This image shows a selected curved node in the middle of a 3-node path; its handles coming in and going out indicate the travel of the stitches. The handle coming in is in a line with the handle going out, thus the curve is quite smooth at the node – it is almost like the node is not there, other than to direct the path.

Remember, smooth curves are created by at least three nodes: an initial starting node, a middle node that the curve runs through, and an ending node. You can click a long smooth curve that runs though as many nodes in the middle as you want, but naturally there’s always a start and an end.

The alternative to a smooth curve is to have a node that comes ‘in’ from one direction, but leaves in another. This is a ‘cusp.’ Cusps are important, as they make the hard turns where curvy bits intersect – such as the top of a heart or in shapes of leaves, or almost anything in nature.

A cusp allows you to have

two curves come together on either side of a point. For instance the apex in the

top, center of a heart-shape is a cusp. Traditionally digitizers would make a

curve that falls just short of the cusp and then make a line to the cusp, and

then they would begin a new curve going off to the other side. This has the

negative effect of that hard line being visible, especially when scaled. It also

produces a needle penetration where it isn’t needed. We’ll discuss more on this

later.

A cusp allows you to have

two curves come together on either side of a point. For instance the apex in the

top, center of a heart-shape is a cusp. Traditionally digitizers would make a

curve that falls just short of the cusp and then make a line to the cusp, and

then they would begin a new curve going off to the other side. This has the

negative effect of that hard line being visible, especially when scaled. It also

produces a needle penetration where it isn’t needed. We’ll discuss more on this

later.

Use nodes where the path switches from turning left-to-right or vice versa. And then when turning, place a node at the ‘widest’ point in the turn if you need an additional node. This will yield the fewest number of nodes needed to make the shape. Remember you can add nodes later, or adjust the curves, if you need to refine the shape.

It is good to use minimal nodes to complete your shape, and then go back and edit the curves to get the shape you want. The result will be a nicer object shape and better embroidery. It takes practice, but you’ll find that you can quickly analyze a shape and create it in very few clicks, and then the edits required will be much easier.

Normally in graphics a “Closed” shape or outline means that its start and its end meet up visibly. A shape that is closed can contain stitches within, and can also have “holes.”

When drawing a shape for

embroidery, you may wish to have the end-point meet up with the start-point

without calling the shape “Closed.” For this purpose, there is a button on the

tool pane which lets you specify that a shape is closed or not. Only closed

shapes can contain holes.

When drawing a shape for

embroidery, you may wish to have the end-point meet up with the start-point

without calling the shape “Closed.” For this purpose, there is a button on the

tool pane which lets you specify that a shape is closed or not. Only closed

shapes can contain holes.

You can open an outline by clicking the ‘Close/Open Outline’ button up. You will not see a change in the shape, but you can now move the head and tail nodes away from each other. The tail node will be red.

If you have a node selected when you open the outline, that node becomes the new head/tail of the outline.

The Point Input method is the most commonly used method, and for most people, it is the easiest. Click the Point button in the Tool Pane and then start clicking along the line you wish to make.

As you create your shape,

you can create curved nodes with a normal left-click, line nodes are made by

holding the ‘Ctrl’ key during a left click, and cusps are made by holding the

‘Shift’ key down during a left click.

As you create your shape,

you can create curved nodes with a normal left-click, line nodes are made by

holding the ‘Ctrl’ key during a left click, and cusps are made by holding the

‘Shift’ key down during a left click.

You can use the ‘backspace’ or ‘Delete’ to remove points you have entered. You can cancel the drawing using the ‘Esc’ or ‘Escape’ key.

When you have completed your shape, you can end it by right-clicking. If you wish to end the shape and also close the outline at the same time, hold the ‘ctrl’ key while right clicking.

While entering points along the outline, you do not need to worry about the Bezier handles – they are created for you using some ‘reasonable’ values. Once you have created your shape, if you want to adjust the handles, you can. Or you can ignore them entirely if you prefer. We’ll talk about that shortly, in the ‘Editing Outlines’ section, subtitled “Working as Spline/Bezier”

This sounds like the most

fun input method, and it is, but it is far from accurate. The freehand input

lets you doodle. You hold the mouse down and drag around. Where you went gets

smoothed out and turned into a curving path. You can click for a line to a

point, and then drag along some more. You can drag and release any number of

times to create lengthy and intricate paths if you wish.

This sounds like the most

fun input method, and it is, but it is far from accurate. The freehand input

lets you doodle. You hold the mouse down and drag around. Where you went gets

smoothed out and turned into a curving path. You can click for a line to a

point, and then drag along some more. You can drag and release any number of

times to create lengthy and intricate paths if you wish.

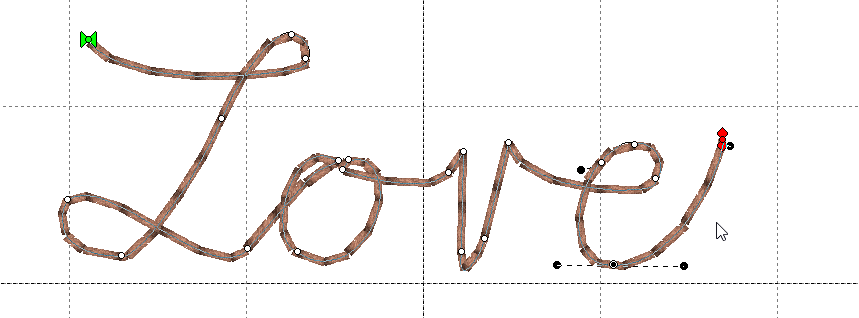

This is useful in practicality only with the Run stitch type. Drawing freehand on a computer requires practice, and the more fluid your input is, the better the result will be. Do expect to spend some time cleaning up your handwriting!

As with other input methods, right-click to end your input. Holding the ‘Ctrl’ key when right-clicking will close the shape.

Bezier Input (Level 2)

The professional graphics

industry has adopted this method of input and it takes getting used to. Select

the Bezier Input method using the button on the Tool Pane. To begin, click and

drag. This will create an initial Node and a Bezier handle. The next time you

click and drag, you will be creating the points needed to complete a Bezier

curve section, and also begin the next one.

The professional graphics

industry has adopted this method of input and it takes getting used to. Select

the Bezier Input method using the button on the Tool Pane. To begin, click and

drag. This will create an initial Node and a Bezier handle. The next time you

click and drag, you will be creating the points needed to complete a Bezier

curve section, and also begin the next one.

If you simply click, you will create a flat curve – a line.

To create a cusp, hold the ‘ctrl’ key down when you click and drag.

Right-click to end your input. Holding the ‘Ctrl’ key when right-clicking will close the shape.

We have made the editing of outlines work in two modes, Bezier and Spline. To understand spline, imagine something flexible, but with a little bit of spring to it – in the original context a spline was a light piece of wood that could be shaped around things. In this use, it is a line that flexes around ‘Nodes’ on the screen (where you have clicked). The more clicks you give, the tighter the spline will have to bend in order to conform to the shape you want.

Bezier lets you adjust the curves using handles, as we have discussed. Now you get to decide how you will perform your edits.

The Spline/Bezier button

on the Tool Pane will toggle all the selected objects to either show their

handles, or hide them. Remember, if you switch handles off, the outline will

change to its automatic shape, and you may have to add some nodes in order to

recover the curves. Spline mode will almost always require more nodes than

Bezier.

The Spline/Bezier button

on the Tool Pane will toggle all the selected objects to either show their

handles, or hide them. Remember, if you switch handles off, the outline will

change to its automatic shape, and you may have to add some nodes in order to

recover the curves. Spline mode will almost always require more nodes than

Bezier.

If no objects are selected, this button also sets how your next objects will be treated, once drawn. This button also acts as a program preference, so if you choose to always work with Bezier, the next time you run the program this will determine the state in which you start.

You can select a node by clicking on it. You can use the Ctrl key while clicking to select multiple nodes. If a selected node is clicked with the Ctrl key it will be de-selected, as is typical with virtually all computer systems.

You can also select nodes by dragging around them. First, select the object that you would like to edit. Then drag around the nodes you want. When you release your mouse button, the nodes inside the area you dragged will be selected.

You can also operate on holes, carving lines and breaklines in this manner – drag around the nodes you wish to adjust.

Double click on the outline to insert a node. Double click on a node to remove it. If you have a node or nodes selected, you can also use the ‘Delete’ key to remove them.

You can switch the type of any selected nodes by right-clicking, which will bring up a pop-up menu. The node types are Curve, Line and Cusp, as we have discussed. Remember that a curve will allow stitches to pass through it without forcing the needle to stop at the node, but by necessity of the shape, lines and cusps will cause the needle to land on those nodes.

Sometimes an inclination line will be made very near a node. If that node is moved so that the inclination line is left in empty space, the incline will be removed automatically. We suggest you adjust your outlines first, then go back and add and adjust your inclination lines.

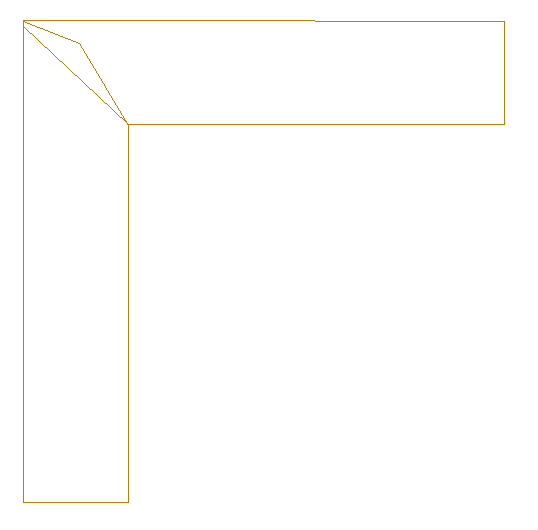

Sometimes you will obtain a file that claims to be in vector form, but is actually an auto-traced image. These are common from clip-art websites, even the big ones. This leaves a series of nodes touching each other as they go around the outline. You can use the menu ‘Create->Outline->Reconstruct Outline’ to simplify the artwork.

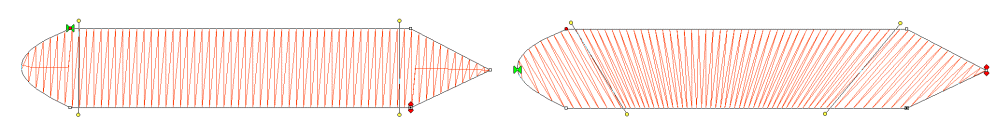

Left: before. Right: After Reconstruct Outline

Spline mode has the ability to insert and remove nodes to adjust the shape. If the curve is too far away from the outline you want, simply add more points on the outline where the shape you have is ‘most different’ or furthest away from the artwork.

It is often best to begin with minimal nodes in the outline, only basically representing the shape you are drawing. Then, go back and insert only the nodes that are needed to pull the outline into shape. Doing it this way, you will use a minimum of nodes.

Why use a minimum of nodes? The stitches being generated have to look at all the nodes on your shape. If you insert hard nodes or cusps, the needle will penetrate at those nodes, so you get less desirable embroidery and an increased stitch count. Another reason to use minimal nodes is for editing purposes. Suppose you test sew your design and realize you need move overlap for registration issues – the fewer nodes, the easier and faster the edits can be accomplished.

Editing paths with Bezier handles exposed is not hard, and is very intuitive once you get past the first few minutes or so.

Editing is accomplished by dragging the handles, which adjusts the curve as you drag. You can also drag the outline itself into place, which will adjust the handles for you. When dragging the outline, the closer you are to a node, the more that node’s handle will be adjusted, rather than the one you are farther away from. Because this can make your handles go ‘wild’ we do not let the outline drag if you grabbed it within 5% of the ends of the outline in either direction. It is best to grab the curve somewhere in the middle and drag it, then adjust the handles to perfect the shape.

Note: Sometimes art will have the handles ‘hidden’ under the nodes. Drag the outline and the handles will move, exposing them so you can drag them around as needed.

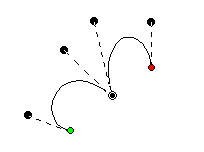

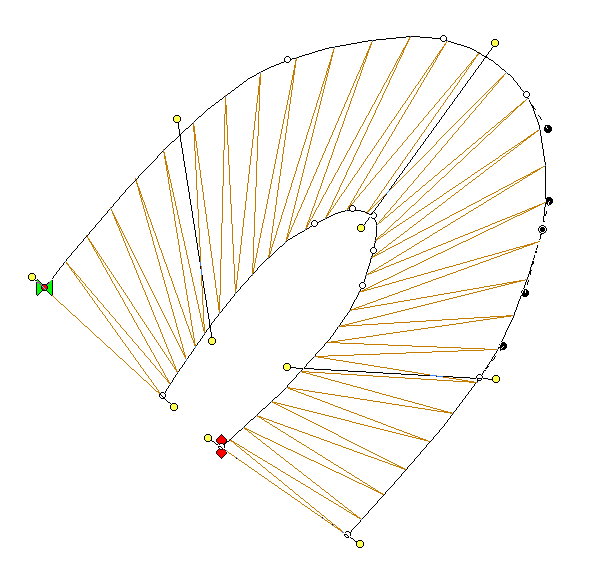

Here’s a step-by-step example of making use of minimal nodes while drawing, and good use of re-shaping: Make a heart, starting at the bottom, using all Cusps (Shift key). You only need four points! Ctrl-right-click to close the outline:

Next, hover your mouse over the curve in between the top left two points as shown, and drag the curve up. You will see the shape beginning to appear. Repeat the drag for the other side. In the example above, we’ve made the sides smooth too. Do any editing desired for the overall image, and you have a low-node-count shape that looks great!

There are also some tricks which we would like to share.

Trick 1: A favorite old movie of ours, Ghostbusters has the line, “Don’t cross the streams!” In the movie, it implied that ‘Bad Things’ could happen. What we’re saying here is, “Don’t cross the handles.” It’s not that you cannot cross the handles – you can – but certain object types will not understand what it is you’ve done. So we discourage it.

Trick 2: Another thing to consider is that the handles should generally be in the direction of the travel of the path. If you have your handles pointing away from the travel of the stitches, then the stitches may do a “Two-Step” which you might not want to happen.

Trick 3: Sometimes you will inadvertently wind up with a handle hidden under the node it is attached to: it is a handle with no length. You can recover these by mousing-down in the middle of the curve and dragging the outline, which reorients the handles for the curve you are dragging. Once the handles are exposed, you can position them as needed.

Trick 4: Use nodes where the path switches from turning left-to-right or vice versa. And then when turning, place a node at the ‘widest’ point in the turn if you need an additional node. If you have extras, you can delete those and adjust as desired.

Holes or ‘voids’ can be

added to artwork for stitch types that use them such as Fills.

Holes or ‘voids’ can be

added to artwork for stitch types that use them such as Fills.

In order to be able to add a hole to a shape it must not only appear closed, but actually be closed. You can tell by looking at the ‘Close outline’ button on the Tool Pane when the object is selected. If the button appears depressed, the shape is closed. If not, you can click the button to close the shape.

Not all stitch types allow holes. When it is allowed, the ‘Add Hole’ button on the Tool Pane will be enabled. You can push this button and then begin drawing the hole. Right click to complete your drawing as with any drawing operation. To add another one, simply click the button again. There are no limits to the number of voided areas (holes) that can be on a shape.

The hotkey for adding a hole to the currently selected object is ‘o’.

If you have drawn several objects, or used path operations to create them and you want to combine holes from multiple objects, select all the objects and use the menu Create->Outline ->Combine Holes.

Holes can be removed by selecting a node on the hole and using the right-click pop-up menu entry, “Delete Hole.” To remove all holes from an object at once use the menu ‘Create->Delete Holes’.

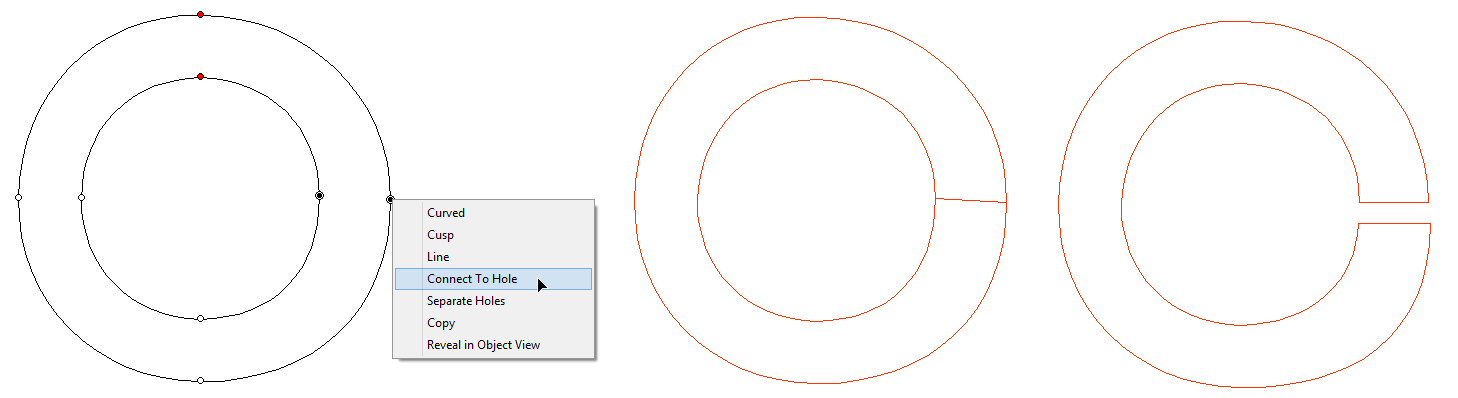

Similarly you can separate the hole into a new object, as an outline, with the right-click pop-up menu entry, “Separate Hole.”

If you have multiple objects with original art that has holes, but you would like to separate them out as individual objects, use the menu Create->Outline->Separate Holes.

When you have two or more lines that should be connected, use the menu Create->Outline->Connect to make them into a single line. While you are drawing, it can happen that you end the drawing before the outline is fully created. You can simply create the rest of the line as a separate object, then select both and connect them.

When connecting lines, the head and tail of the first line in the sequence are preserved, and thereafter the lines that are being connected to it will be reversed as needed to ensure the nearest connecting point. You do not need to have your line endpoints adjacent, as a connecting line will be added for you if needed.

When you create a line, there is a point where you started and a point where you ended. If you wish to reverse the direction of points on the line, use the menu Create->Outline->Reverse Points.

Generally, the outline order is not very important for the creation of stitches. You may, however want to use this when working on connecting shapes you have made.

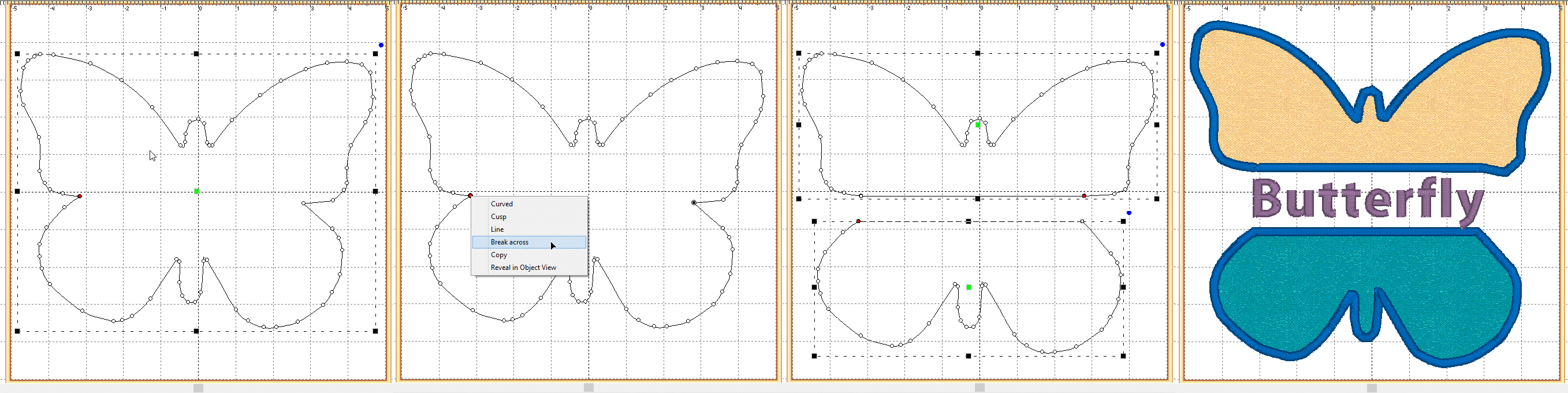

You can select two points across a closed outline and break the outline into two using the context menu option ‘Break across’. This is sometimes useful in logo or promotional designs, where you have original shapes, but want to separate them and insert a word or other design element in between.

If you have an open shape selected, with one or more nodes in it selected, the context menu option, ‘Break at point’ will split the object into multiple objects.

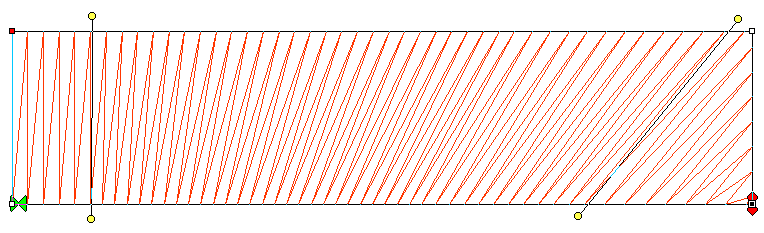

Sometimes you’ll need to turn a shape with a hole into a continuous outline, such as to make a satin stitch. To accomplish this, select two near points, one on the outline and one on the hole. Then use the context item, ‘Connect to hole.’ The hole is now part of the outline, as shown:

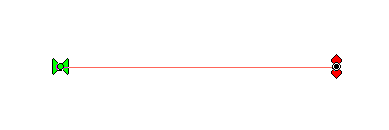

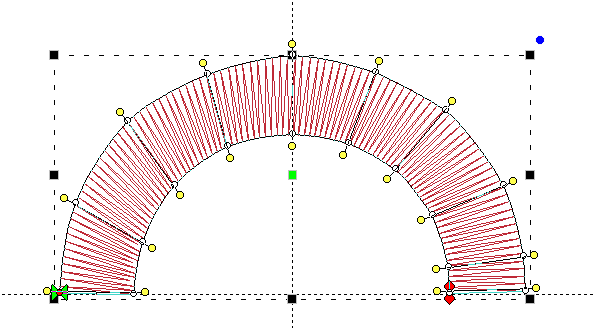

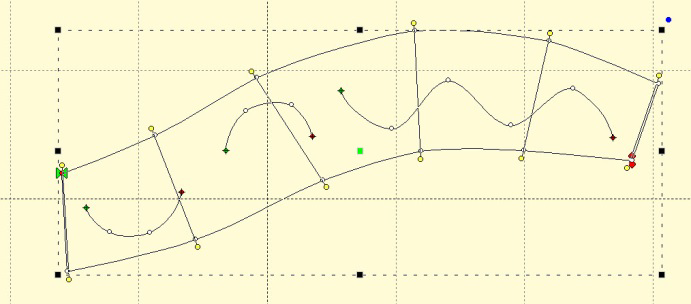

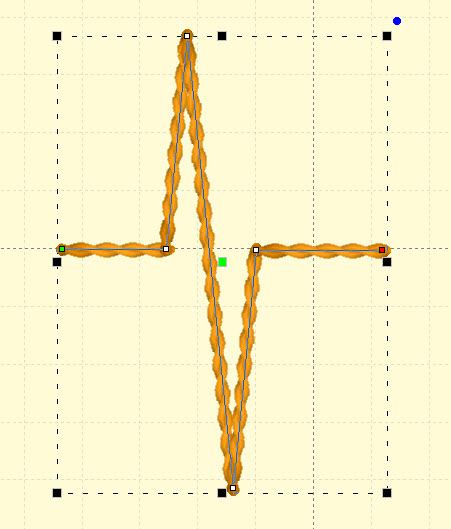

While not directly used

in defining a shape itself, there are Entry and Exit points that accompany

outlines once a stitch object type has been assigned.

While not directly used

in defining a shape itself, there are Entry and Exit points that accompany

outlines once a stitch object type has been assigned.

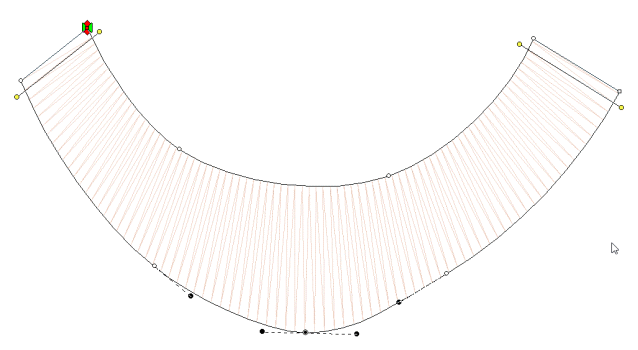

These Entry and Exit points indicate the preferred location of the beginning and ending of the stitching process. In the illustration, the stitching would begin at the green handle on the left, and finish up at the red handle on the right. You can drag the handles around anywhere on the outline. You cannot drag them to a hole, if the shape has one.

There are some object types where the stitching follows an algorithm that comes back to a single point. Those object types are noted in their respective sections. Entry and exit points are used to limit the number of jump stitches in a design. By having the objects end and begin at near-most points, the transition stitch between the objects is minimized.

The Entry point on an object is where the stitching will begin, and Exit is where the stitching will complete. The purpose of adjusting the entry and exit is to minimize (or eliminate) traveling runs needed to move from one object to the next. This also lowers the stitch count.

Note: Usually you will want to set the Entry and Exit points after you have sequenced your objects.

Most stitch generation has the availability of adjustable Entry and Exit points, although some only use the Exit such as Stippling, where stitching is continuous.

Entry and Exit adjustments are usually not noticeable in the resulting stitches except for Runs. Runs by definition have styles such as Single, Double, Bean, etc. When you have a single run enter and exit at the same point, you are going to have a double-run result. The exit handle forces the stitches to run to the exit, over top of what’s been stitched. This can be handy when creating redwork or running-stitch designs as you may set the Exit Handle as needed, and not worry about changing the property to a double.

Entry and Exit on a stitch object are controlled by the green (Entry) and red (Exit) handles on the outline of the object. Drag the handles to the point on the outline as desired. Generation of stitches is automatic.

Use the menu Create->Auto Entry/Exit to set the Entry and Exit handles on selected objects. The ‘Automatic’ process looks for the nearest points on the objects if they don’t touch, or to a point where they touch, if they do.

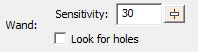

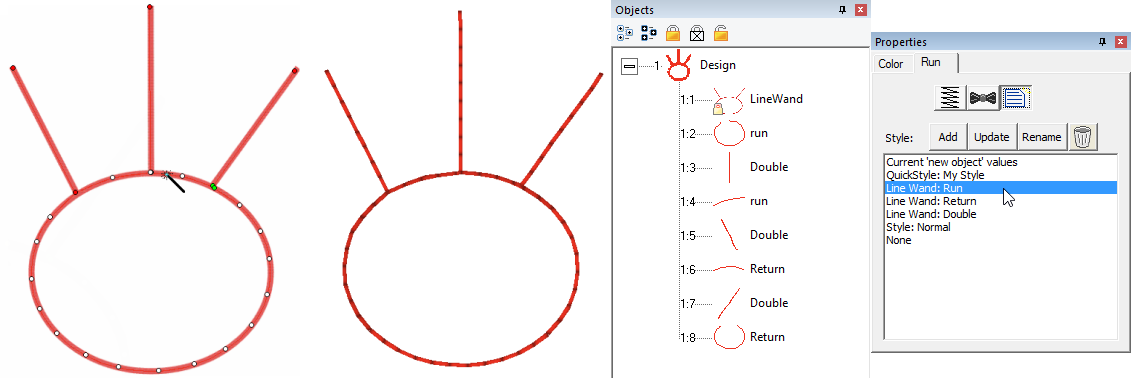

The Magic Wand is a tool

used to create outlines from bitmap images. There are two styles – a wand for

filled areas, and a wand for lines. The Line Wand tool is available in Level

3.

The Magic Wand is a tool

used to create outlines from bitmap images. There are two styles – a wand for

filled areas, and a wand for lines. The Line Wand tool is available in Level

3.

When you turn on the Magic Wand, you can click on the backdrop image and the Wand will look at the color where you clicked, find all pixels (dots) around it with a similar color, and then make an outline out of all of those similarly-colored pixels. The shape that a Magic Wand creates will not be as clean as one drawn by hand, but they are fully editable, and can be an effective way to get started on some simple projects.

Note: When you like the wand result, right-click to end the wand to keep what you’ve made. If you click the Wand button again, or hit the ‘Esc’ key, you cancel the operation.

Because images differ in quality, when you click on the wand, the Sensitivity controls will appear. A low number of sensitivity means the pixels it is looking for will be very similar to the one on which you clicked. If you have an image with a mottled texture, for instance a piece of scanned fabric in the picture, you can make the sensitivity large, for example use 150, and the outline will be expanded to include more pixels to get a better outline.

As you adjust the sensitivity the wand will re-wand where you clicked automatically. You do not need to click again.

Important: When you like the wand result, right-click to end the wand and keep what you’ve made.

The wands will create as many objects or holes as you like. Once your sensitivity has been adjusted and you have an outline you like, simply click the wand again in another area to begin making a new object. Right-click to end object creation once all objects have been wanded.

Expand the Object View to watch the objects get created – sometimes a higher sensitivity will result in fewer objects or outline nodes, which is desirable. Other times, higher sensitivity can add ‘noise’ in the edge, or even fail to find a shape at all when the outline and background are similar.

The first wand button creates an outline around areas filled with a consistent color.

You can also use the wand during an ‘Add Hole’ operation.

Normal graphic fills, such as those from a cartoon image will not need a high sensitivity to the color used. You can reasonably use the default number. If the image is scanned from a print, you might need to increase the sensitivity a little. Try different levels to see what you get. Note that some large images with a high value for sensitivity can take longer to wand.

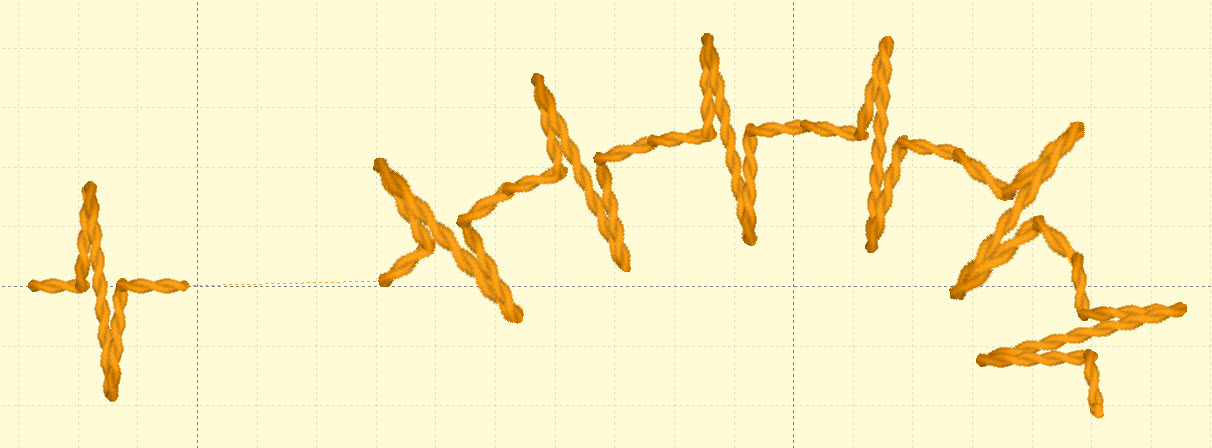

The second Magic Wand is for line drawings and line areas in a cartoon-style image. The color you click on has all of its pixels gathered and thinned to make a running-stitch object. The line drawing may be very complex, and the Line Wand will create as many objects as it needs to in order to stitch around the entire design doubly. This is useful for automatic outline or redwork designs. The Line Wand will set all the Entry and Exits and create a double-run design ready to sew.

The objects that are created also have Styles used. You can adjust these styles, thus adjusting the style of the result. Please refer to the Styles section for details.

To further explain; let’s examine a simple ‘T’ shape that might represent any ordinary outline drawing. The Line Wand will find a starting point, run to the ‘T’. Now it has to go both directions in order to sew the entire shape. To do this, it will run out on one side first. Then run back. This process repeats for the second side. Now that this part of the path is complete, it can return to where it started. In this way, the entire design has been stitched over twice.

If you don’t want the entire design branched in this fashion, the objects created are editable – you can do what you like. Also, the objects have styles named for what they are doing within the path. By changing objects labeled ‘Run’ you are changing the run out – not anything with topstitches. Change the ‘Double’ for branches that are open-ended – they run out and back. Change the ‘Return’ for topstitching as the stitching comes back over itself.

Some bitmap images will be like an old black-and-white television image, and we call those grayscale. When you load a grayscale image, the chances are good that the image will have lines that look nice and clean, but are really all sorts of gray variations, like a pencil drawing. Grayscale images are fine to work over, but if you plan to use a magic wand line input you may want to save the image as a Black and White (1-bit) image, if you have an image-editing program such as Paint.

Basic cut/copy/paste operations are supported, and there are some additions you’ll want to know about especially for sequencing the design, as we’ll discuss shortly.

When you cut, you are removing items from the design page. Pasting them puts them back, and keeps a copy in memory so you can paste multiple times, even on multiple design pages.

As we have discussed, there are Designs, and there are Objects. Designs contain objects, so when you cut, copy or paste a design, you are doing it to an entire design including all the objects within it. Pasting a design will place it at the end of the sequence on the design page (visually at the bottom of the Object View list.)

Pasting objects will place them at the bottom of the last design in the sequence, unless you immediately precede the paste with a menu->Create->Design->Set Current Design.

When you cut or copy something for a paste, its location on the design page is stored with it. When you paste, either on the same page or another, that location is used for the paste – it will paste in the same place. However, if you have a new location in view, say you are zoomed to a new area of work, and the original location is not visible, the center of the current view is where the paste will occur. This helps minimize the amount of moving-around of pasted items you will need to perform. Simply zoom in comfortably to the location where you would like the items pasted, and Paste (or ‘Ctrl-v’).

You can decide where to paste objects by selecting a ‘target’ object, and then right-clicking on it in the Main View. You will have the option to ‘Paste Under’, ‘Paste Over’ or ‘Paste Replace’.

Pasting Under will paste the cut/copied items before the first selected item in the sequence (the pasted items will sew first). Pasting After will add them after the last selected item in the sequence.

Paste replace is a special feature. If you have a design element that’s being used repeatedly, you may have pasted it into multiple places. But what happens if you later discover that you need to edit that element? Perhaps the stitching needed to be changed, or a connective run was missing from the original. You can fix this by copying the revised element, then selecting an item it is to replace, and Paste Replace will remove the item selected and replace it with the copied one. It will be centered where the original was, and it will be in the sequence in the same place as the original item.

This is also useful for placeholders while you are creating. Suppose you know you’ll need a flower, “Here, there and there.” You can simply insert an object to mark the locations of those, and Paste Replace them later.

An especially useful feature to help with this is ‘Grouping.’ If the element contains multiple objects, group them using the Edit menu or ‘Ctrl-G’. When pasting the first time, paste the grouped objects. Later, when you perform a ‘Paste Replace’, you will first select the destination group by clicking on it in the Main View and perform the ‘Paste Replace.’ This selects the entire group and will remove that entire group when you Paste Replace.

Objects can be grouped so that when you select one in the Main View, all will be selected together for operations such as Move, Rotate, Mirror, Cut/Copy/Paste, etc.

Use the Edit menu->Group or ‘Ctrl-g’ for this.

Note: When items are grouped, they are still individually selectable in the Object View, and can be edited singly if selected.

If you have a design selected when grouping is performed, the design is part of the group. This means sequencing and copy/paste operations will be done at the design level. If you want all the objects from a design, but not the design itself, make sure to check the Object View to see that the design is not selected.

The Edit menu->Ungroup (Ctrl-u) can be used to ungroup objects.

You can group selections that contain sub-groups. Ungrouping will not ungroup the sub-groups – those will have to be ungrouped with a separate ungroup command.

The sewing order of the design is very important. You don’t want your design to sew randomly all over the fabric. It will leave jumps, or have increased trims, or worse, increased color changes, and if you sell designs, your customers won’t be happy.

There are ‘best practices’ for sequencing on different embroidered goods, most notably hats. If you’re creating a design for a hat, you’ll want to attempt to sew from the center outward. This helps keep the fabric in place and flat in the hat frame.

For regular designs, it can often be useful to have stitching work the edges of the design first, in effect anchoring the stabilizer, then work from the center out.

Think about how you would like the design to sew. You’ve probably watched hundreds of designs stitching out, and you can use that experience to help you decide what to sew in what order. Things that connect are pretty easy to figure out – you want them to sew without jump stitches, usually. If you are new to embroidery, we recommend you spend some time embroidering so you can get used to the stitching process. If you can look at a complete design, figure out what object types were used to make it, and predict which objects will sew in what order, then you are ready to take on sequencing.

Work on the sequence on a per color basis. There is always a trim when the machine goes to the next color, so imagine your machine working one color at a time. And yes, there are times when it is necessary and even a good idea to revisit a color – you don’t have to put all your colored objects together. Layering and Shading are good reasons to separate a color into sections with different colors in between.

Once you have a sequence in your mind, you’ll need to adjust the objects to match. And for that, you’ll need to know how to change the sequence your design.

The Object View shows you the sequence of your objects in the design. You may have a lot of objects for a complex design, and that’s normal. If the design can be broken down into separate designs themselves it may be helpful. For instance if you have a picture of a flower and a butterfly, you might make them separate designs on the page, and create them separately.

When you right-click on an object in the Object View, you get a pop-up menu which lets you move designs in the sequence. This is often handy for simple or small moves.